Before Michelle Cruz Gonzales earned a BA and MFA from Mills College, she was the drummer in the 1990’s all-female hardcore punk band Spitboy and people called her Todd. Or sometimes, the Female Phil Collins of Punk Rock Drummers because she sang and played drums at the same time.

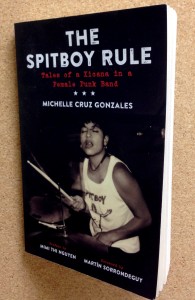

In her 2016 memoir, “The Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band,” Cruz Gonzales offers an intimate, analytical and inspiring account of her years playing in Spitboy and other bands.

Spitboy commanded respect in the Bay Area punk scene and toured internationally, but the tense intersections of race, gender, sexuality and social class tested Cruz Gonzales’ patience.

She recalls how, being a female drummer, she was approached after nearly every show by young men saying the same thing: “You hit hard for a girl.”

“The comment made me want to punch each guy who said it in the face,” she writes.

Unapologetic, just like punk music has always been, Cruz Gonzales directly addresses the strengths and shortcomings of the punk scene, punk values, her fellow band members and the band’s decisions, like choosing not to align with the riot grrrl movement that was growing at the same time.

Spitboy was not riot grrrl band. Riot grrrl was a small, fierce, important scene of female punks who made space for girls to be loud on stage and empowered in the audience, but Spitboy resisted being pigeonholed as riot grrrl or a “female punk band.” They were a hardcore punk band, regardless of being female.

“We were one of the only all-female punk bands playing straight forward hardcore, no jangly chords, reverb, or feminine harmonies for us,” Cruz Gonzales writes.

She discusses how her identity as Xicana, and as a person of color from a family on welfare in a rural California town, was persistently invisible in the largely white punk scene. In one chapter, she describes how a white riot grrrl in Olympia accused Spitboy of cultural appropriation for naming their 7-inch release “Mi Cuerpo Es Mío.”

“She objected to our use of Spanish for the title of our record and accused us of stealing from someone else’s culture, in particular the words ‘mi cuerpo es mío,’ which translates to ‘my body is mine.’ Apparently my body was invisible,” Cruz Gonzales writes.

Like claiming control over their own bodies, the Spitwomen insisted on control over their own band. They did everything themselves: made their own merch by thrifting T-shirts and screenprinting the Spitboy logo, fixed their own van when it broke down, changed their own tires, set up their own gear and hustled it offstage after their sets.

The Spitboy rule was “no boyfriends on tour” until they toured Europe. There, they allowed male roadie-boyfriends to help out and accepted help and kindness from other punk bands, like when a member of legacy punk band Subhumans made the Spitwomen tea between shows.

The photographs and show flyers throughout the 132 page book give vivid insight to Spitboy’s shows, recording sessions and international tours. The book is available in the F.W. Olin Library, and is best accompanied by a box of punk records and record player, or an online playlist, of Spitboy songs and 1990’s underground hardcore anarcho-punk.

Cruz Gonzales, along with Andrea Wolf (Andrea Abi-Karam), will read at The Contemporary Writers Series annual alumni reading on Tuesday, April 10 in the Mills Hall Living Room at 5:30 p.m.