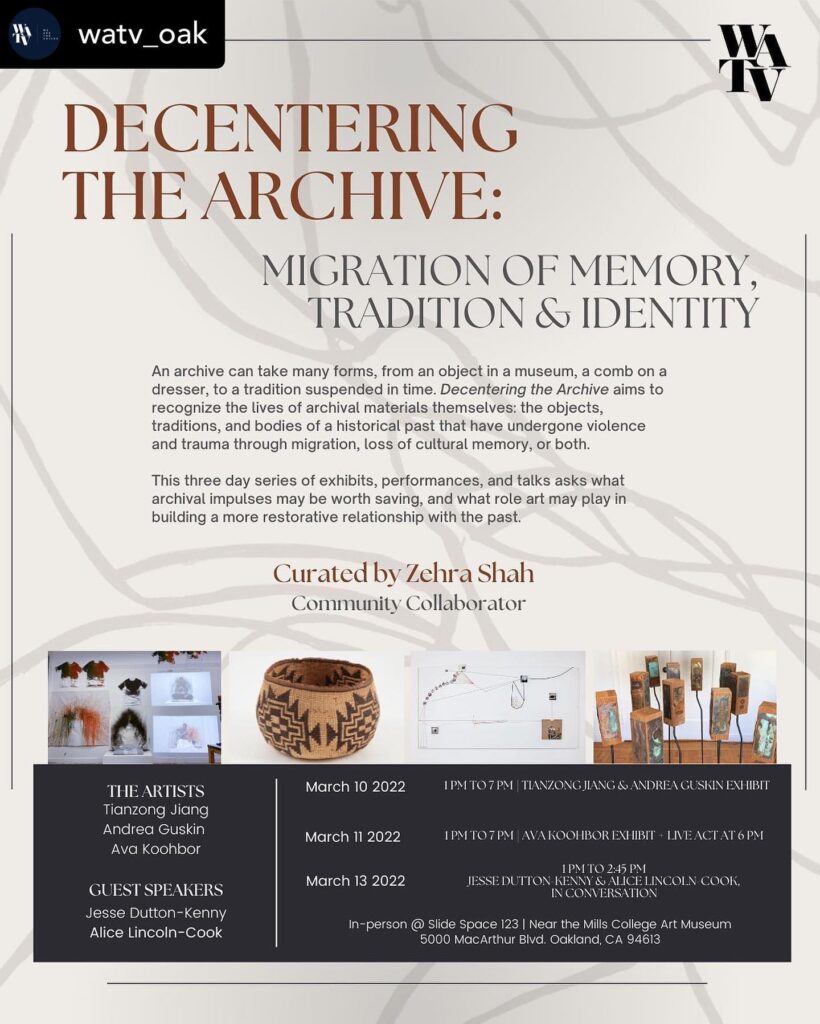

March 11, 2022, may have been the first day that Mills’ gallery Slide Space 123 had electronic music machines, a full-sized typewriter and a shawl knitted out of copper wires in the same room. This dazzling display was all made by one artist, Ava Koohbor, for curator Zehra Shah’s three-day exhibit, “Decentering the Archive: Migration of Memory, Tradition & Identity.”

Shah is a poet, writer and oral historian obtaining a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing with a specialization in poetry. Her exhibit imagined the purpose of an archive beyond rows of carefully cataloged artifacts and expanses of Excel columns. She “aims to recognize the lives of archival materials themselves: the objects, traditions, and bodies of a historical past that have undergone violence and trauma through migration, loss of cultural memory, or both.” A deep sense of purpose underlies Shah’s work — she wants to explore the role of archives in “building a more restorative relationship with the past.”

Koohbor is one of several artists Shah curated for Decentering the Archive. Besides being a fellow poet and Mills student, Koohbor was a natural fit for Shah’s exhibit because her art focuses on the themes of memory and bicultural experiences. Koohbor, originally from Tehran, Iran, came to Mills to pursue a Master of Fine Art in electronic music. However, her art spans several disciplines. She is not only a musician but a poet, a studio artist, and, at least on March 11, a dancer. Rather than existing separately, all of Koohbor’s artistic mediums meshed together to create one exhibit.

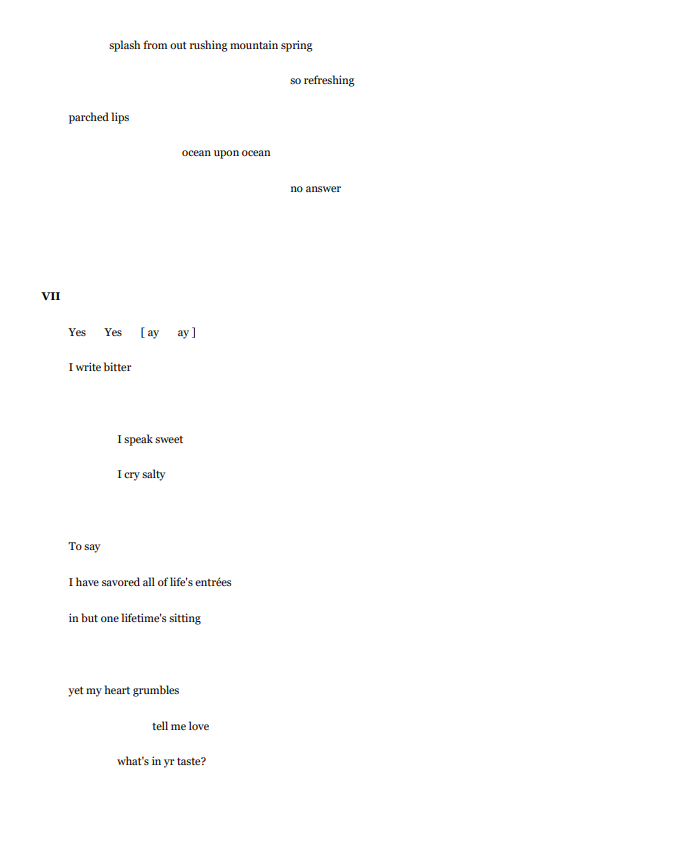

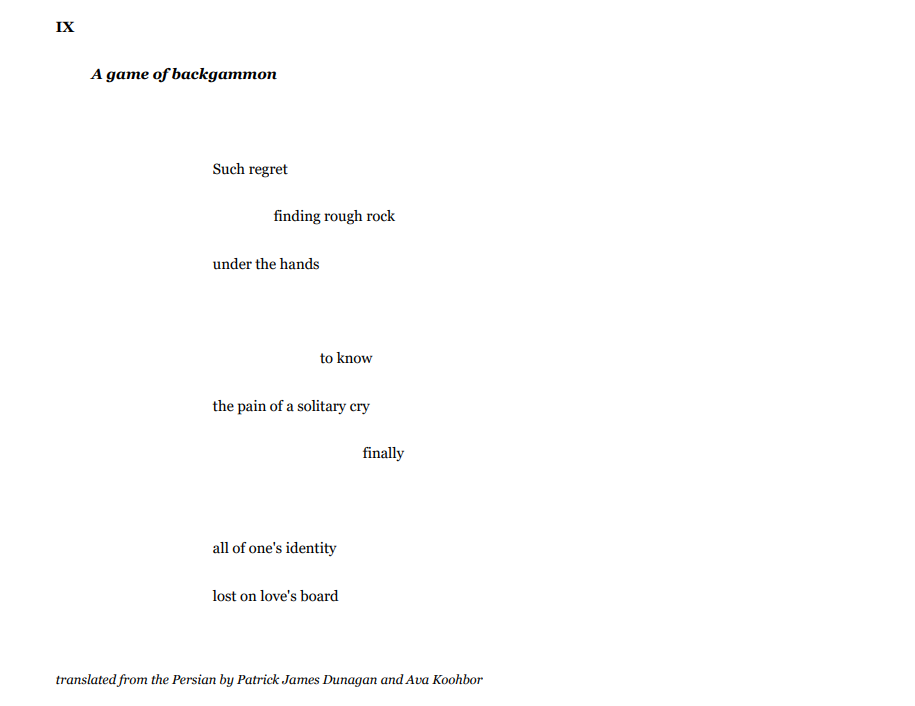

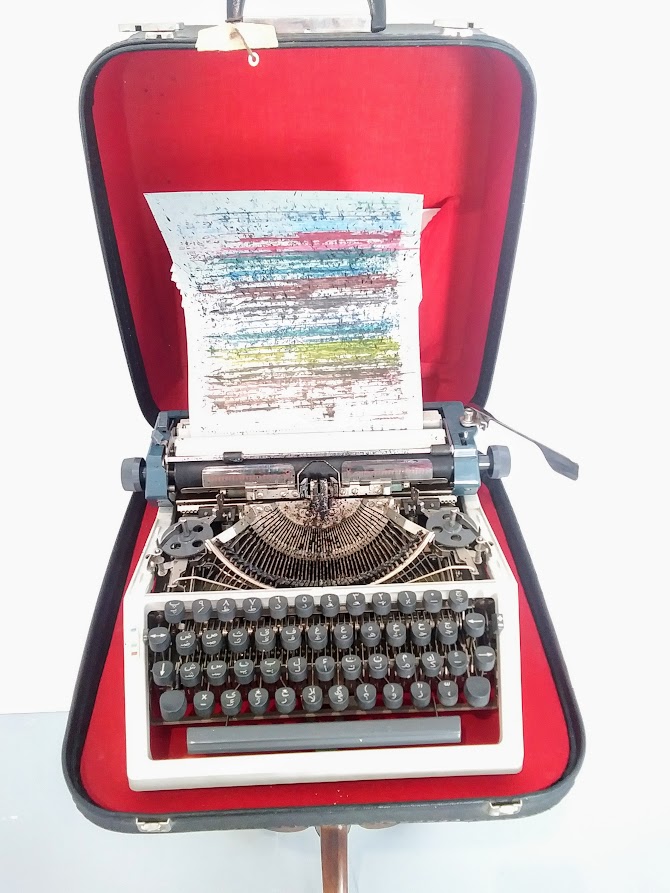

The walls were adorned with studio art pieces, each unique. While each piece was distinctive, Koohbor’s fascination with copper was evident in its recurring usage. On one wall, smooth sheets of metal created a mesmerizing sheen, catching light and reflections from every angle. On another stood a typewriter with a printed poem typed in several layered colors of ink. Koohbor also displayed a web she had knitted of copper wires enclosing several metal balls, which she would later wear on her back for an in-house dance, spoken poetry, and music performance. Finally, the site of her live performance beckoned to viewers with an electronic music setup. In front of the music machines, multiple sheets of copper were mounted onto small wooden blocks held up by metal poles, similar in structure to a lamp (see the photo in the flyer above). Here was the heart of her archive.

The metal shawl. Photo courtesy of Ava Koohbor

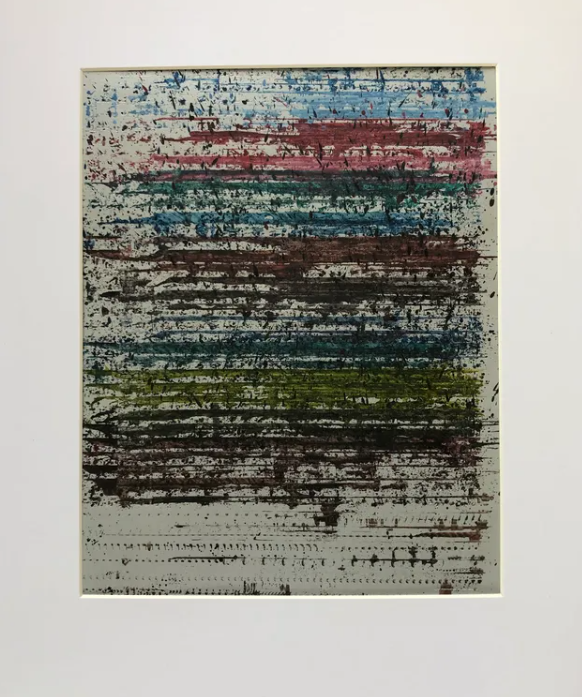

Photo by Iris Kingery

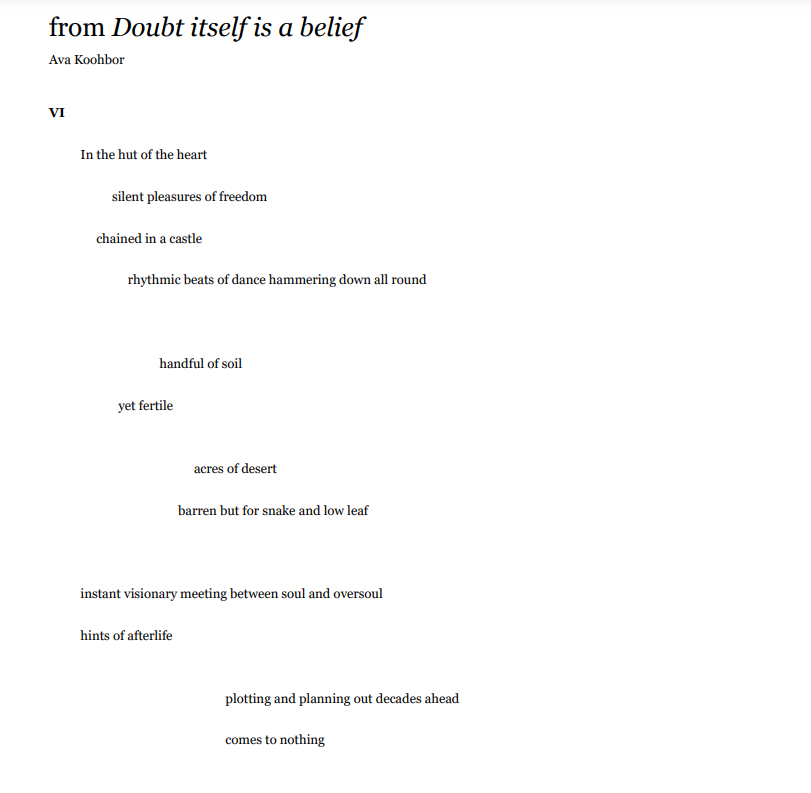

The poem from the typewriter. Photo courtesy of Ava Koohbor

The typewriter. Photo by Iris Kingery

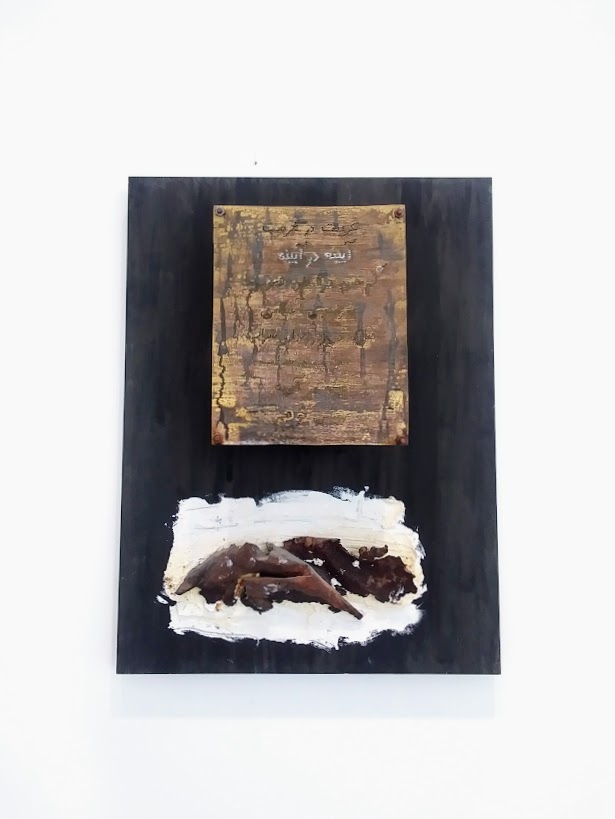

Copper poetry. Photo by Iris Kingery

A copper poem up close. Photo by Iris Kingery

When asked in what way she considers her work an archive, Koohbor nodded to the sheets of copper, which were engraved with poetry in Farsi. The sheets were far from pristine; instead, they’d been allowed to oxidize, giving them a beautiful blue and gold marble effect. To her, this method of recording her poetry is an archive. “[…] art is about bringing art into existence and from then on, [letting] them form themselves. They are becoming just a presence of themselves. I’m not controlling,” she said. Her archive is about the allowance of aging.

Koohbor also mentioned alchemy, which she says is a common theme in Iranian poetry. “People were also obsessed with alchemy, for example. They wanted to make a mixture of life [and become] eternal.” She believes that working with copper symbolizes humanity’s quest for everlasting youth. “[Humanity] wants to turn copper to gold, and also make an elixir of life. So it’s in our psyche, I think.”

But Koohbor wants to offer a different perspective on aging with her art. She believes that the adoration of youth can cause more pain and conflict than choosing to appreciate the passage of time. She commented, “Usually, aging comes also with wisdom. What we want to get from [aging is in] how we perceive it. The wars that human beings are obsessed with just kind of just depends on the definition that they choose.”

On language, Koohbor shared, “I also write in English, so I do most of my poetry readings in English. And sometimes I kind of suprise myself [with] the emotion that comes out. Every time [the emotion] comes differently based on how you feel the audience. Who are you reading for?” She said that the emotions she feels towards her writing change based on her familiarity and intimacy with the audience.

“Each language has their own capability,” Koohbor noted. She describes speaking English as an experience of increasing consciousness on her part, turning from unconscious to conscious as she speaks it more. She says that there can be “in-between spaces” where she doesn’t know which language to use. Even the mechanics of the two languages are different — English is written left to right while Farsi is written right to left. Even with these differences, the parts of Koohbor’s exhibit harmonized as one entity, symbolizing the greater theme of a full life inhabiting an “in-between” space.

At the end of the evening, Koohbor gave her in-house performance. Her poetry’s raw, emotional recitation was overlayed with an original electronic music piece, creating an intricate soundscape. While wearing the copper shawl, she weaved through the poetry sheets with strikingly emotive movements, coming to kneel and pray to the music machines. After the applause, attendees were left with a lesson: to honestly inhabit “in-between” spaces and embrace the natural flow of life.