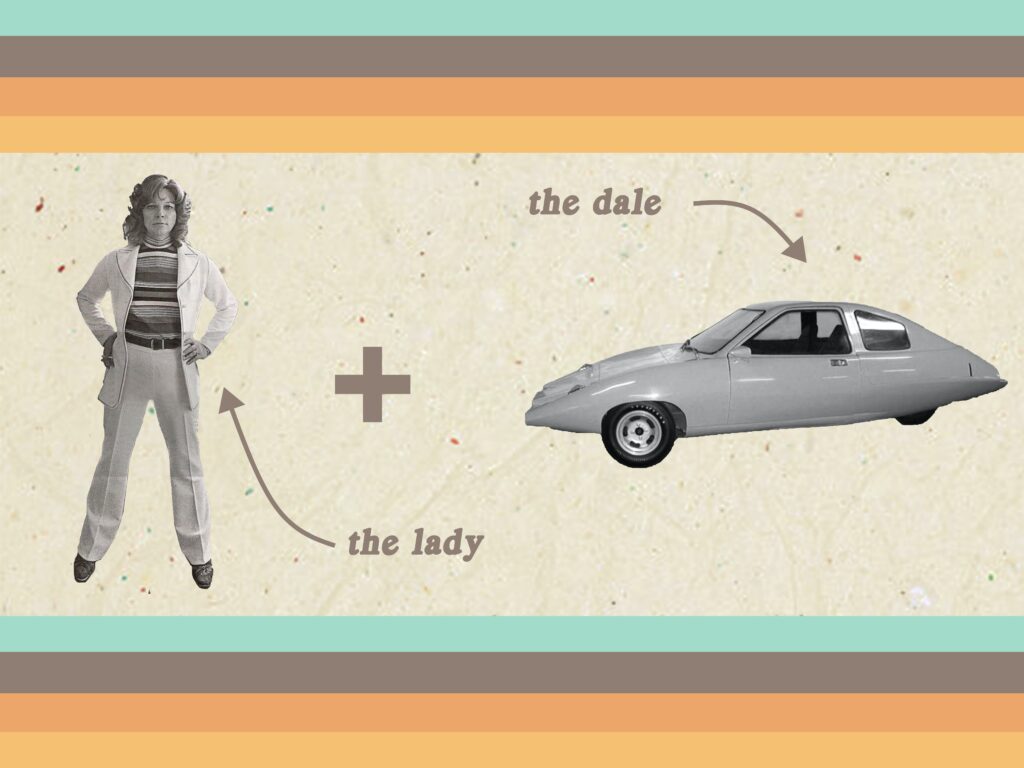

HBO’s recently released docuseries, “The Lady and the Dale,” tells the story of a woman who wanted to become a billionaire, a transgender and feminist icon, and eventually, the president of the United States. But today, she’s best remembered as a con artist — when she’s remembered at all. This documentary’s titular “lady” is former automobile executive Geraldine Elizabeth “Liz” Carmichael, known for her promotion of a three-wheeled car called the Dale. With a mileage of up to 70 miles per gallon, the Dale car promised Americans a solution to the gas crisis of the 1970s. When Carmichael failed to deliver on that promise, the resulting media scrutiny made public a number of secrets that would follow her the rest of her life — not only about her car or her company, but about her criminal past and her gender transition.

Though all this information is revealed within the first few minutes of episode one, “Soldier of Fortune,” the show quickly rewinds to Carmichael’s childhood in Indiana and moves forward from there. We are taken through the years she spent traveling around the lower 48, during which she married, reproduced with, and left various women. She also took part in a wide variety of crimes for ambition and profit — culminating in a scheme to produce counterfeit cash, which caused the federal government to issue a warrant against her. At that tipping point, Carmichael officially went on the run, along with her final wife Vivian and their brood of children. Some years into their flight, she decided to transition, coming out to her family and beginning to publicly present as female. The episode concludes when Carmichael obtains the rights to the Dale car from its inventor and leaves her job to form the Twentieth Century Motor Car Corporation. The second episode, “Caveat Emptor: Let the Buyer Beware,” opens on the meteoric rise of Twentieth Century Motors, bolstered by charismatic Carmichael’s false claims about her background in engineering and the superb abilities of the Dale car. An investigation into the company, launched by journalists Dick Carlson and Pete Noyes, revealed that its funding came largely from illegal financial practices. The resulting backlash, plus a failed attempt to secure new funding from Japanese investors, meant Carmichael’s employees were no longer earning the money they’d been promised.

Episode three (“The Guilty Fleeth”) sees the whole of Twentieth Century motors charged with conspiracy to commit grand theft in selling and promoting the Dale, and Liz Carmichael not only arrested but publicly outed after a search for her whereabouts unearthed evidence of her transgender status. Much of the episode focuses on her imprisonment and court case, during which she defended herself and represented herself as innocent of all charges. After being found guilty, she once again skipped town with her family, leaving open warrants for her arrest. The finale, “Celestial Bodies,” shows Carmichael’s re-arrest after a 1989 episode of “Unsolved Mysteries” resulted in her being recognized by a viewer and reported to the police. It also documents her founding of a thriving flower-selling business, and its disruption by another reporter who connected her to her past; and finally, her eventual death from cancer.

“The Lady and the Dale” presents its sprawling, variegated storyline by way of an equally variegated set of visual and auditory devices. It most prominently uses old photographs of our main players, their black-and-white or sepia heads cut-and-pasted onto cartoon bodies and moving their mouths like marionettes. Also in attendance are a wide variety of video clips, ranging from televised interviews with Carmichael to scenes from old movies; frequent talking-head interviews with Carmichael’s children, employees, friends and enemies, plus a few experts in fields relevant to Carmichael’s life; and recordings of Carmichael’s voice and writings. These cinematic devices have earned praise from multiple news outlets for their novelty and visual appeal but garnered criticism from others as confusing, insufficiently serious or otherwise unsuitable for the subject matter. Animation director Sean Donnelly says that although the production team always intended to tell parts of Carmichael’s story with animation, its use was ramped up after the onset of COVID-19 to compensate for the inability to film live segments.

While its visuals can read as peculiarly lighthearted, “Lady and the Dale” unquestionably takes itself seriously on the subject of transgender representation. True, Liz Carmichael is frequently deadnamed and misgendered by video clips and interviewees — not only by unsympathetic reporters, jurors or police, but often by her own family members, which can be painful to watch, particularly when her life before her transition is on display. But the show tries to put these interpretations of her identity into context at every step. This is clear not only in the treatment of those who would out Carmichael (for instance, footage used in the show reveals that transphobic Dick Carlson is the father of conservative commentator Tucker Carlson, a connection used to discredit both Carlsons’ stances

Stryker, who currently holds the Barbara Lee Distinguished Chair in Women’s Leadership at Mills College, is the most prominently featured of these three. In her screen time, she establishes a history of early

Some reviewers argue that the show overreaches in its attempts to respect Carmichael’s transness, asking the audience to admire her as a trans icon. While it’s hard not to develop some liking for this charismatic, confident woman — the interviews demonstrate the depth of the love and loyalty she engendered, with family and former employees expressing deep affection for her years after her passing — it’s equally hard to forget how many people she deceived, how many lives she had some negative impact on, and how morally wrong it is that she legally named one of her sons “Michael Michael.”

“The Lady and the Dale” tackles a profoundly complex life, and whether it manages to fully represent Geraldine Elizabeth Carmichael in all her nuance is up for debate. But if you’d like to join in that debate, or just spend an evening catching up on the not-so-distant past of gender and cars, you can stream all four hour-long episodes of the show on HBO Max.