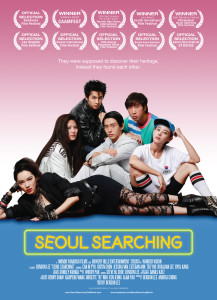

The six main characters messily learned about themselves in Seoul Searching. From left to right, Grace (jessika Van), Kris (Rosalina Lee), Sid (Justin Chon), Klaus (Teo Yoo), Sergio (Esteban Ahn), and Sue-jin (Byeol Kang).

With the recent rise in Asian American creative productions (think Crazy Rich Asians, 88 Rising, Mindy Kaling, Aziz Ansari, Fresh off the Boat and Netflix specials with comedians like Jo Koy, Ali Wong), I’ve been exploring more and more contemporary artists, and I hope this is a rise that will continue indefinitely.

Although I’d love to talk about Ali Wong, 88 Rising and the rest, that’s for another article. Instead, I’d like to introduce you to the sublime coming-of-age, summer-camp, rom-com, travel movie rolled into one: Seoul Searching. Oh, and it’s also unabashedly Asian American.

It’s the summer of 1986, and the Korean government has created a summer camp to host teenagers of Korean descent from countries around the world as a way to reconnect with their heritage. From the moment the six main characters step off the plane into the airport, it becomes clear that this summer will be one they’ll never forget. Filled with irresponsible partying, adolescent insecurities, and the joys and pains of growing up, these six stories will sweep you up along the way.

Within a more easily digestible movie format lies the deep, complex heart of Seoul Searching. It takes the classic tropes — punk anarchist kid, preacher’s rebel daughter — and gives them another dimension. As the cheesy title might suggest, this movie veers into the predictable. Yes, some points are clichéd. Yes, sometimes the dialogue is a touch ham handed. But it still made me cry. And laugh.

What I love about this movie are the themes that it touches on through these characters. From the minute they step off the plane, it is glaringly apparent that the Korean instructors are not prepared for these boisterous, rebellious, conflicted kids. Klaus struggles with feeling, in turns, both proud and embarrassed of his immigrant parents. Grace is a lot of things, everything except being sober. Sergio and Sue-Jin wrestle (sometimes literally) with the concept of masculinity in traditional Korean culture and how that has played out in their lives. Sid has deep-seated hurt about his father; Mike is racist (yes, Asians can definitely be racist), and grapples with his, I would argue, toxic masculinity. And Kris, my favorite, finds her birth mother, which is a somewhat unrealistic but also heart-wrenching plot point.

Some might find that the sometimes-a-little-too-obvious script relies on just stereotypes to drive the interest. I disagree. While the script can stray into being too ham-handed, I find the stereotypes that the characters loosely embody to not be a detriment but instead a revelation of how useless those stereotypes are, how multifaceted people are and how people are built in part by their environment. It wasn’t the use of stereotypes just for the sake of it, it was a use in order to deconstruct.

And in some ways, the use of those stereotypes — the Californian punk anarchist, the military kid, the messed up alcoholic, the girl next door, etc. — are used strategically to explore the diversity of America. There are Asian American military kids, alcoholics, girls next door, Asian American punk anarchists. This movie is validation that YES, Asian Americans can be all these things — and MORE! We can be kind, tough, sexy, quiet, loud, emotional, overjoyed, inhibited, messed up, uninhibited, fun, incredibly smart, wild; we can be anything.

We can be Asian Americans, Asian Germans, Asian Mexicans. The diaspora is global.

One thing I appreciate about this movie is that a lot of the actors actually represent the characters they’re playing, or very closely, which is a kudos to casting. Teo Yoo, who plays Klaus, is actually Korean German; Justin Chon, who plays Sid, and Jessika Van, who plays Grace, are actually Korean American; Esteban Ahn, who plays Sergio, is not from Mexico, but from Spain and can speak Spanish as he does in the movie; Sue Son, who plays Sara Han, is truly a Korean Brit; Cha In-Pyo is a South Korean actor and he plays the students’ Korean instructor. The other actors all seem to be of Korean heritage. This is impressive because of how common minorities play other minority roles — mostly because the lack of acting opportunities. Either that, or whitewashing.

The cast included Afro-asian celebrity Crystal Kay. Unfortunately, Seoul Searching perpetuated anti-black portrayals.

One of my favorite moments in the movie *SPOILER* was when our main characters get into a fight, instigated by Mike (who is racist against the Japanese for basically the whole movie) with another group of teenagers who were visiting from Japan. It turns out that those teenagers were also kids of Korean descent who grew up in Japan. They were also returning to Korea. It was a great reminder of similarities and seemed to give Mike more insight and something to reflect upon in relation to his own racist views.

The idea of the “homeland” and what you may gain from “returning” is so complex. Will it restore you? Will you find something? Find yourself? Will you understand your parents better? Your heritage? Will you become a “real” Korean? I’m adopted internationally, so the idea of being able to go back to, or even welcomed by, the “motherland” is a fascinating and intoxicating idea.

If I’m being honest, there’s a few things I’d have liked to see. One, more lines and character development for Jamie, who is Blasian (also known as Afro-Asian), meaning a mixed race person of African and Asian descent. Very rarely are Blasians represented onscreen, let alone at all, so I think that was a huge missed opportunity. Second, I’d like to have at least one character who was gay, or LGBTQ+. Sue-jin and Sergio did gender-bend at the summer camp dance, but that’s about as far as this movie pushed.

Third, there were a few characters who were into freestyle rapping and hip-hop, but the way they were portrayed felt appropriative and offensive (they did use the N word) instead of representational. Of course there are Asian Americans who like hip hop and rap themselves, but this felt like too much of a stereotype, and nothing deeper. Not being Black, I didn’t know how this would come across to someone who is, but then I found a review by Black Nerd Problems. Read Lauren Bullock’s review of how anti-Black she felt Seoul Searching was.

Seoul Searching hit theaters in 2015, so this kind of sloppiness, insensitivity and poor writing felt completely outdated and very, very wrong. Lastly, as I mentioned before, sometimes the script was a little obvious and clunky.

Like Lauren Bullock covered, this film has issues. I didn’t realize how big those issues were until I read her review, so please head over and read her article.

Ultimately, for me, my appreciation of Seoul Searching comes down to an idea she mentioned in her piece: this movie provides a vision of American films that could be, and offers a narrative where there is a clear gap in American media. It gives representation in a rarely addressed topic, and centers Asian American stories in the lens.