It’s the middle of the night and I’ve been in the studio for hours, since well before the dinner break I barely took. The wide windows reveal a spooky, pitch black darkness outside while I clean the press and put away all my tools and materials. My feet are sore from standing so long, my back is aching from leaning over the press, and my eyes are tired from closely studying the tiny metal minutiae of my layout.

But none of this matters, because waiting for me on the drying rack is a suite of gorgeous prints created by me from start to finish. Tomorrow those prints will be folded, glued, sewn and bound into artist books, and I’ll forget all about the aches they brought about.

My own work joins a greater conversation in the field of book art, a field where concept meets form.

On the College Book Art Association webpage, Kathleen Walkup, professor and head of the Mills book art department, writes about what artist books mean today. “When text is woven into the conceptual fabric of the book, the whole can become far greater than the sum of its parts, ” Walkup said. “[Artist books are] books that understand their own operation, their iconicity, their materials and their content as an interwoven whole.”

At Mills College, the book art department teaches students to “place [their] work in a conceptual and historical context” in “one of the oldest and most established Book Art programs in the country,” according to the promotional material published by the school. So as Mills is considering a shift in their curriculum toward the 21st century with the transformation of some existing programs and the creation of new ones, why is book art faced with the threat of closure?

In a proposal to close the book art program in their latest round of budget cuts, supposedly to make room for the creation of newer and more contemporary departments, the administration and Board of Trustees are making the implicit argument that artists’ books are obsolete and irrelevant as Mills transforms itself for the 21st century. In response, a community of people, both those working in the field of book art and their supporters alike, are rallying to refute that claim.

In this age of increasing digitalization, and as the relevance of the physical book is being questioned more and more, book art transforms the commonplace book into an artistic cultural artifact, one which connects the mind and body in a physical practice. Not only this, but the practice itself provides visual and tactile training which equips students with skills that will serve them in a range of other innovative, contemporary fields.

Kate Robinson, an MFA graduate from Mills Class of 2013, has been working in print and letterpress communities in various forms across the country since her graduation and now works as the collections associate at the Letterform Archive in San Francisco.

“Print media, and book art specifically, is not dead,” Robinson said. “In fact, I believe it is on the brink of a watershed moment of innovation.”

In response to the proposed closure of the program, letters of support have been pouring in. The letters are from Mills students and alumnae, but the list doesn’t stop there; other similar programs throughout the country, artists working in the field and prestigious libraries around the world, including the Astor Curator of Printed Books and Bindings at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, are among the throng of supporters that have gathered in the two weeks since the administration’s announcement. What’s most remarkable about these letters, Walkup says, is that none of them were solicited by the department.

In one such letter, Aaron Cohick, a book art professor from Colorado College, expresses his admiration for the book art program at Mills and defends the vital significance and relevance of the form, saying it “takes the material and conceptual production of the book as a critical nexus point” from which artists engage in thoughtful, interdisciplinary investigations from which to launch long-term, thoughtful, multi/inter-disciplinary investigations.” Walkup agrees. In book art though, much of the work is conceptual, incorporating text, image, history and theory; she says artists go on to realize concepts through the hand and the body.

A post on the “Save Mills Book Art” Tumblr page, where countless individuals have gathered to share insights and testimonials in response to the threat to the program says of book art: “It’s a place where verbal and visual arts combine and can train individuals not only to develop a deeper literacy of their own, but to help foster that literacy through the projects they create and send out into the world.”

Mirabelle Jones, a graduate of Mills’ MFA program in creative writing and book art, describes the program as “the first to recognize writer-artists as complex, multi-talented individuals who refuse to separate their artistic practice from their writing practice. “As book artists,” she says, “our writing becomes an essential part of our artwork.”

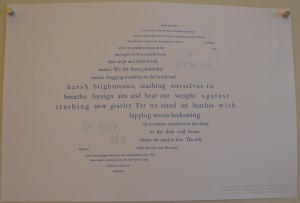

Book art as a form not only provides the artist with new ways to approach writing, but it also teaches reader-observers to interact with books in a new way. Current MFA student Ariel Strong says that book art “invites audiences to look at a historical technology in new ways.” She says book art can be an exciting blend of many things: history and technology, structure, material, text and typography, image and sequence. It allows a person to “have a singular relationship with a work of art, to hold it in your hands and view it intimately.”

Karen Bleitz, Mills Class of 2009, makes interactive books which draw in their readers by encouraging them to manipulate the page: books with magnets, pop-ups and machines, become stages where the reader is invited to be an active participant in the reading experience. According to the “arc Unbound” catalogue which showcases her work, “the transformations that take place within the pages force her readers to ‘re-view’ and experience the subjects from a changed perspective.”

The discipline of book art not only continuously challenges divisions between form and content, between writer, artist and audience, but the training it provides for those things also forges a deep cross-connection to disciplines and industries we might not expect.

Alyssa M. Alcorn, Mills Class of 2009, studied book art at Mills and is now finishing her doctorate at the University of Edinburgh in human-computer interaction.

“I absolutely believe that my years in the book arts studio were an important foundation for my current work in design, research and teaching,” Alcorm wrote on the Mills Book Art Tumblr page. “Book Art taught me about design thinking, making choices and justifying decisions when there are 101 options, project planning, and the virtue of measuring twice and cutting once.”

The intellectual skills and the training to make clear aesthetic choices are skills which book art provides its students and which are immediately translatable to other fields in the twenty first century.

Book art is a thriving, well-established, historically significant program at Mills; this fact is indisputable. And if the outpouring of support and glowing testimonials is any indication, the field of book art will continue to thrive. The question facing us now is not whether book art will be included in Mills vision going forward; rather, the question facing us now is whether Mills will sustain its place in the 21st century by preserving this historic and innovative program.