For several decades, the world of classical music performance has been in a panic. Audiences have aged and dwindled, ticket sales have declined, and orchestras have faced fierce competition for scarce philanthropic dollars. Many have wondered aloud about the demise of an age-old tradition. At a 2008 TED conference, conductor Benjamin Zander summarized the dismal outlook pervading the music profession: “They say three percent of the population likes classical music. ‘If only we could move it to four percent, our problems would be over!’”

In the prevailing narrative of classical music’s impending doom, professional orchestras play a starring role. Anxious attention is lavished upon its supposed harbingers, like the recent liquidation of the Honolulu Symphony and the Detroit Symphony’s four-month musicians’ strike. Even warhorses like the New York Philharmonic and the Philadelphia Orchestra have seen drastic budget cuts in their struggles to remain solvent.

The evidence is mounting: professional orchestras are no longer the unshakable cultural institutions they once were. Maintaining them on life support is no longer a viable option. In fact, a save-the-orchestras mentality is likely to do more harm than good. If the tradition of classical music performance is to survive the next century, it must be liberated from the confines of the concert hall. To take on new life, it must reach new ears.

Moving beyond the concert hall requires a fundamental reorientation for classical music’s patrons and practitioners. Many are mired in a dogmatic (and historically unsound) allegiance to the concert hall, refusing to see film music and contemporary genre-mixing as legitimate branches of the classical music tradition. Yet it is precisely this rigidity that makes the concert hall a hostile setting for new listeners. A strict code of behaviors and protocols governs the concert hall, reinforcing a sense of classical music’s elitism. The novice concertgoer who offers applause between movements is almost certain to receive a few cold glares.

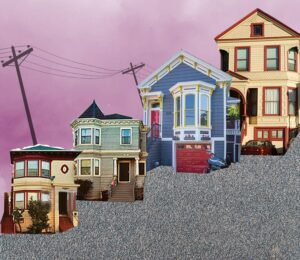

In his TED talk, Zander rightly insisted that four percent will never cut it. The future of classical music hinges on making performances accessible and relevant to the other 97% of the population. Some groups have adopted this philosophy and pioneered ventures into new musical spaces. The Metropolitan Opera has made live broadcasts available in movie theaters worldwide. An even more promising direction is the return of classical music to familiar, everyday spaces. The San Francisco-based Classical Revolution offers chamber music performances in cafes, bars, and even at Food Not Bombs dinners.

In its golden age, classical music was a living art form. Legends of Beethoven’s improvisation contests evoke a spirit of creativity and democratic participation that may be more recognizable in today’s freestyle rap contests than in the concert hall. For classical music to move beyond the concert hall, the music establishment will have to contend with the disruption of cherished traditions. Both music and performance practices will be cut up, altered, and remixed. But for those who love classical music and wish to see it thrive, perhaps a bit of change is welcome.