Photographer: JOSE LUIS MAGANA / AP

Washington D.C. – On Saturday, Aug. 28, 2021, an estimated 50,000 people participated in a voters’ rights march organized by Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network and 180 partner organizations. Marchers were calling on the Senate to pass the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2021, CBS News reports.

The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, named after the late Georgia representative, passed the House on Tuesday, Aug. 24, with a 219-212 vote going along party lines.

This bill restores a 1965 Voting Rights Act, section 5 provision that requires specific jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination in voting to receive the approval of what’s known as the “preclearance formula”, which was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2013, from the Department of Justice prior to changes to their voting rules. This portion of the bill was designed to ensure that voting changes in jurisdictions covered by section 5 could not be implemented until a favorable determination has been obtained. Covered jurisdictions are identified in Section 4 of the bill, which focuses on how some jurisdictions in the past used discriminatory factors that the state or political subdivision of the state maintained on November 1, 1964, such as “literacy tests” and complex, interlocking systems used to deny African-Americans, Latinx and Indigenous people the right to vote. These drastic measures ensured that political power remained exclusively “white-only” by instituting reading requirements for illiterate people or forcing those discriminated against to recite the American Constitution verbatim.

Other methods of discrimination and intimidation included:

A “poll tax,” or a tax that is required to be paid prior to voting. State and local poll taxes were common, but mainly limited to the Southern states by the mid-20th century as a means of preventing Black people and poor whites from voting.

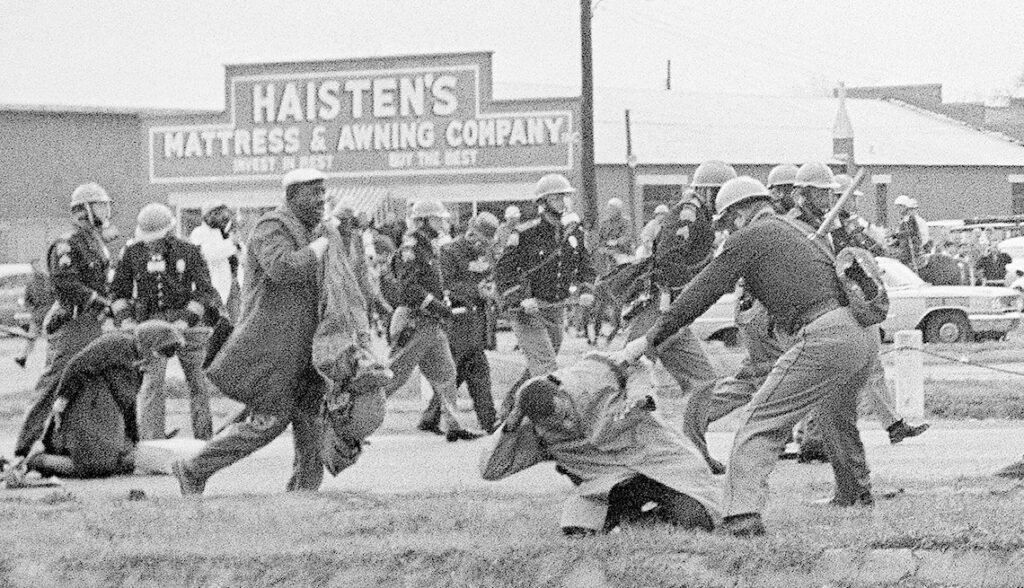

Physical force, combined with police intimidation, was often implemented to discourage voting. Various state, county and local police forces would regularly intimidate and harass Blacks Americans, often with physical violence or unlawful arrest, when they attempted voter registration. Some of their harassment tactics included arrest with false charges, severe beatings and, in extreme cases, murder. This kind of retribution was directed at both men and women, as well as their family members and children once the names of the Black Americans attempting voter registration were made known to police. This method was often combined with white terrorism. Some in law enforcement were members of the Ku Klux Klan who engaged in cross-burnings, night raids, beatings, raping women and young girls, church bombings, arson of private residences and businesses, mass murders, lynching, drive-by shootings and sniper assassinations. Today these people are the textbook definition of “domestic terrorists,” but in those days, the white establishment saw them as defenders of the “southern way of life” and upholders of “our glorious southern heritage.”

Economic retaliation was an additional layer of discrimination. White businesses, employers, banks and landlords organized into White Citizens’ Councils that agreed to inflict economic retaliation against nonwhites who tried to vote. Their methods of voter suppression included evictions, mass firings, boycotts and forced home foreclosures. Most minorities in the south were small-scale farmers who needed a crop loan each year to purchase seed, fertilizer, fuel and food until they could sell their crops after harvesting. This left them vulnerable to banks who denied much-needed loans to Black people who tried to vote, eventually forcing them off the land.

According to Justice.org, Section 5 was enacted to “freeze changes in election practices or procedures in covered jurisdictions with a history of voter suppression and racial discrimination, until the new procedures have been determined, either after administrative review by the Attorney General or after a lawsuit before the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, to have neither discriminatory purpose or effect.”

This ruling meant that the rest of the Voting Rights Act continued to exist, but the preclearance portion could no longer occur until Congress drafted a more relevant formula based on “current conditions.”

According to the Brennan Center for Justice, the Supreme Court ruled in 2013 that it was unconstitutional for the Voting Rights Act to use information labeled as “decades-old data and eradicated practices” as the modern-day basis for selecting which states are forced to adhere to preclearance guidelines. Later, the Court struck down the coverage formula in a narrowly won 5-4 vote during the Shelby County v. Holder case.

The constitutionality of the Voting Rights Act Section 5 was challenged and upheld in May 2012. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit agreed with district court that Section 5 was constitutional.

Shelby County appealed the ruling to the Supreme Court, and the Supreme Court agreed to take the case in November 2012. The Supreme Court eventually ruled against the key section 5 provision. This opened the door for continued assaults on voters rights soon after the ruling throughout the nation, allowing formerly restricted states to implement new voting restrictions without obtaining federal permission first, CNN reports.

Under Section 5, any change with respect to voting in a covered jurisdiction, or any political subunit within it, cannot legally be enforced unless and until the jurisdiction obtains the requisite determination outlined by the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, then makes a submission request to the Attorney General. This measure was added in order to ensure that states would have to provide proof that the proposed voting change would not “deny or abridge the right to vote on account of race, color, or membership in a language minority group.” Should the jurisdiction fail to prove the absence of such discrimination, the District Court has the right to deny the requested judgment, or in the case of administrative submissions, the Attorney General can object to the change, that will then remain legally unenforceable.

Every state, regardless of whether it has a history of violations, would have to get federal approval for specific kinds of changes to voting laws. This includes:

A. Tightening voter ID requirements

B. A reduction in voting materials in languages other than English, or, in certain communities that have substantial minority populations

C. Reductions in the number of voting locations or changes to district boundaries, CNN reports.

Currently, the John Lewis bill is on its way to the Senate and facing strong GOP resistance. According to CNN, on Tuesday, Aug. 30, 2021, when asked where he stands on the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) called the measure “unnecessary.”

“What the John Lewis bill does, is grant to the Justice Department almost total ability to determine the voting systems of every state in America,” McConnell said.

A fact check by CNN has confirmed that the 2020 bill would give the Justice Department more power over states’ voting laws than the department currently has. However, it would not require preclearance for every state or every new voting law being proposed. As in the previous preclearance requirement, the proposed 2020 requirement will not allow the Justice Department to “pick and choose” its own preferred voting policies while accepting and rejecting changes proposed by the state.