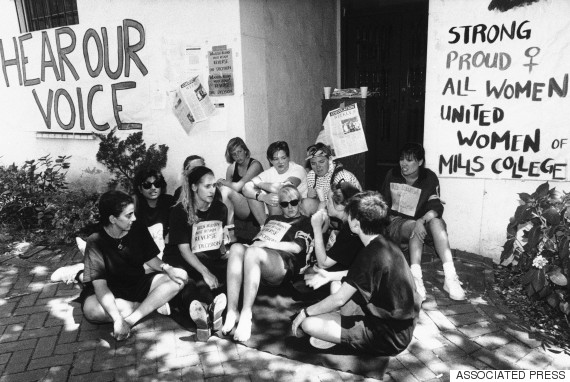

“We will not accept this!” was one of the many chants during the 1990 strike at Mills College when then-Board President Warren Hellman announced the decision to admit men into undergraduate programs. At the time, the Board of Trustees had come to two options — either go co-ed or expand the institution — and considered coeducation the better option in solving the college’s financial instability. Due to the students’ organization and civil disobedience, the decision was overturned.

Since March 2020, several small colleges across the country have closed due to financial challenges that have been worsened by the pandemic, and this week, Mills students are were faced with an upcoming change on their campus.

On Wednesday, March 17, the President’s office announced that Mills College will begin transitioning from a degree-granting institution to a Mills Institute due to the “economic burdens of the COVID-19 pandemic, structural changes across higher education, and Mills’ declining enrollment and budget deficits.” After Fall ‘21, the college will no longer admit or recruit first-year undergraduates. This decision was made by the Mills College Board of Trustees, and it is likely that Mills will grant its final degrees in 2023, pending further consideration by board members.

“While Mills’ role as a degree-granting college will end, its mission will endure. Mills intends to continue to foster women’s leadership and student success, advance gender and racial equity, and cultivate innovative pedagogy, research, and critical thinking by creating a Mills Institute housed here on campus,” President Hillman wrote, “Over the next few months, Mills faculty, trustees, staff, students, alumnae, and other stakeholders across our community will consider potential structures and programming for a Mills Institute.”

In a follow-up to the announcement, the Provost and Dean of Faculty Dr. Julia Chinyere Oparah sent an email to the student body about efforts to support continuing undergraduate and graduate students.

“Graduate students will continue to be enrolled after fall 2021, depending on individual circumstances and degree programs, with the expectation that their programs will be completed by the end of spring 2023,” she wrote.

Guided by Mills’ accrediting agency, Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC), the Provost’s Office plans to create new systems for all degree programs where continuing students will be able to complete their degrees through “a combination of Mills, partner institution and online consortium courses.” Students who won’t graduate before Spring 2023, such as the incoming Class of ‘24, may have other options to transfer as Mills develops new relationships with other small colleges, local independent colleges, and historical black colleges and universities (HBCUs). Starting September 2021, the Office of Admissions will start to help students with their individual transfer plans “by providing streamlined applications and advising.” These transfer opportunities will become available as soon as Spring 2022.

According to Dr. Oparah, UC Berkeley would potentially be a transfer option for students. There are conversations with other historically black women’s colleges, such as Bennett College located in Greensboro, North Carolina and Spelman College based in Atlanta, Georgia.

“We realize that this news likely brings a mix of emotions and concerns. Please know that we are deeply committed to your academic success, and are here to guide and support you through the transition.” Dr. Oparah said.

Amongst feelings of sadness and anguish, students were initially concerned about the validity of their degrees, tuition changes, support for staff and faculty and what a Mills Institute was going to look like. During a town hall held the afternoon of the announcement, senior administrators held a virtual question-and-answer session to share more details and reasoning behind the decision.

“The financial challenges that Mills faces, makes it impossible for us to continue to grant the kind of high quality education that Mills wants to offer to its students,” President Hillman said.

This year, Mills College has an overall budget of about $50 million with a deficit of $3 million. The deficit had been decreased from $14 million through several financial efforts to cover operating costs. Mills sold William Shakespeare’s First Folio, a treasure in the collection, received donations from generous alumni and was authorized by the Board of Trustees to use more of the endowment funds to cover operating costs. College endowment funds are typically restricted to supporting such issues as financial support for teaching, research and public service. Even with a large decrease in the budget deficit, Mills is unable to financially sustain itself. President Hillman expects there to be several educational partnerships in the future.

However, the closing of Mills College would not affect the degrees of graduated students. President Hillman assured that the reputation of the college is longstanding, thus the value of the degrees will remain the same.

At this time, there have been no defined plans for a Mills Institute other than a commitment to ensure a continuation of the College’s mission.

“It means that Mills won’t indefinitely continue to grant degrees, but we’ll continue to pursue its mission in a different forum, not by being an accredited degree-granting college, but instead, by being a place that supports student success, gender, and racial equity and women’s leadership through programs, co-curricular efforts; other initiatives are yet to be designed,” President Hillman said. “… We anticipate a co-design process that will involve many stakeholders to build a Mills Institute.”

While there have been conversations regarding a potential transfer for students to UC Berkeley, there have been no final decisions regarding the expanded partnership introduced to students in October.

Upon receiving the news, students, staff and alumni shared their shock, sadness and frustration via Twitter and MillsGo. For decades, the Mills community has created safe spaces for students and since 2014, Mills has been a pioneer in its admissions process being the first historical women’s college to admit transgender students. For many, Mills is a place to call home.

Sonja Piper Dosti, Class of ‘92 came to Mills from Dallas, Texas and expressed her appreciation for how the college challenged her as a student and her desire for the space to be maintained for students.

“Mills meant opening my world and my viewpoints and my preconceived notions, challenging me and a lot of things that I believed in. And what I loved about Mills was just the diversity of our student body, our passion for human rights, women’s rights, for people of color for people from around the world. And, you know, being there, obviously, we were there during the strike, too,” she said. “Mills just taught me to find my voice and to make sure that I never backed down from the things that I was passionate about.”

A year ago, Piper Dosti and other alumna learned more about the recent financial struggles and declining enrollment during the Class of 1992 luncheon with President Hillman. The president outlined several initiatives being considered such as conversations with UC Berkeley and potentially selling land or assets for additional income.

“So a lot of the ideas she was sharing, felt encouraging, and we thought, ‘Well, Mills is in good hands with President Hillman because she had a passion for Mills’, as an institution for equity and for women and dealing with the issues of gender and race,” Piper Dosti said.

While the news of a Mills transition was a shock, it was not completely surprising as she knew that the college was undergoing financial stress — and the addition of COVID-19 was “the final nail in the casket of Mills.” Piper Dosti plans to continue to support Mills but she and many alumni have questions about what a Mills Institue will look like.

“I don’t want to think ‘Oh, I’m going to withdraw my money now and I’m going to send it to another women’s college’ … I’d rather it still be at Mills, but I need to know what that’s going to look like, and how it will continue to preserve the identity of what Mills has been since 1852. And I know it’s different today than what it was back then but there has still been a heritage of it … just breaking ground in so many different ways,” Piper Dosti said. “… We need to know what we alums need to do. Do we need to mobilize and do something to preserve aspects of Mills? What can we do? And I know there’s already alums that want to be sure that every student who’s there can still get their degree.”

Meredyth Cohen, Judicial Chair of the Associated Students of Mills College (ASMC), felt similarly in regards to the announcement. With conversations around partnerships with other colleges and budget deficits, she understood that there was a strong chance of changes within the institution. She reflects on her time so far in ASMC and having a comfortable space on-campus.

“I felt very comfortable there around having leaders, especially my predecessors … acknowledge me as a leader there. I think ASMC really felt like it was a space where I wasn’t always the person that had to stand up for disabled people and neurodivergent people and things like that,” Cohen said.

However, she understands students’ reactions to wanting to transfer in response to a Mills transition.

“I know a lot of students who want to transfer because one, I think a lot of people feel like their degree won’t hold as much value … that’s definitely a concern. And then I think people also [are] just worried about professors leaving and just like the school not really being able to offer everything,” Cohen said. “And then I think a lot of people just want to transfer because even if they’re in Class of 2023, but let’s say they were on a five-year plan, then they [have] to change.”

Paloma Silva-Navarro is a first-year at Mills whose initial college experience was completely remote. She and many other students in her class are expecting to transfer by or before Spring 2023 as their graduation date is set for 2024. She received the announcement from the President’s Office during her English class.

“We were all full of questions and disbelief at first,” Silva-Navarro said. “… I am still anxious to see how Mills will be able to provide us the support during this rough transition.”

As a high school student, she had visited Mills for the Swim a Mile for Breast Cancer event and found that the college was a space for people from diverse backgrounds.

“I really enjoyed seeing the women’s leadership and encouragement firsthand. Now that I am able to attend Mills College, it feels different,” Silva-Navarro said. “Due to the pandemic, I felt like many other freshmen across California, a disconnect from the community that I thought I would have [been close to]. But I also was able to look out for extracurricular activities such as Latino Heritage Month and my job as an Eco rep. They made me feel closer to Mills’ missions to foster growth and learning.”

After hearing dialogue amongst her peers about what should be done in the aftermath of Mills closing, she believes Mills should consider returning the land to the Indigenous community it was historically stolen from, the Chochenyo Muwekma Ohlone people.

The Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, an indigenous women-led land trust based in the San Francisco Bay Area and Huichin, Ohlone land, shared a post on their Instagram on the day of the announcement. They encouraged Mills to use the opportunity to return the land through the trust.

“Every end could be a new beginning… Mills campus was founded on a former Ohlone village site in 1852 after the Indigenous people who lived there were forcibly removed and enslaved,” the post read. “Actually, every school in this territory is built on stolen land and has benefitted from the displacement of and state sponsored genocide against California Native people. Maybe now is a good time to begin healing a small piece of that history? Hi Mills! We a land trust, hit us up.”

The futures of faculty and staff are also uncertain. They were aware of the history of financial challenges at Mills but knew that President Hillman had been working to establish revenues to alleviate the college’s deficits. Even with the anticipation of change due to conversations regarding expansion, it was unclear what Mills was planning for the future.

On March 10, The Mills Staff Union Organizing Committee submitted questions to President Hillman during a faculty and staff town hall meeting to learn more about what steps were being taken to support staff, faculty and students in an expansion and what decisions were being made with UC Berkeley.

“Supporting staff, faculty and students is absolutely a priority Mills is not Mills without the people who are Mills and we realize that. Continuing to pursue Mills’ mission means also taking care of the people who have been pursuing Mills’ right now. We want to find ways to sustain and create opportunities for people who are here right now,” President Hillman said.

Since the announcement, the Mills Staff Union has scheduled a bargaining session with President Hillman to discuss new concerns staff have regarding plans for an institutional change.

“We’re looking forward to it, we’re grateful for her taking the time to do that,” Kalie Caetano, a member of the Mills Staff Union Organizing Commitee and Bargaining Team, said. “We had been trying to advocate for greater involvement for staff in particular, because that’s who we as the union represent, to have some involvement in these decision making processes. And unfortunately, that just didn’t come to fruition. So, we’re still kind of hoping that we might be able to change this dynamic a little bit and create opportunities for there to be more democratic decision making happening at Mills.”

In a survey conducted by the Mills Staff Union amongst its’ members, they learned that one of the main concerns was job security. The survey was shared to identify staff concerns, what they wanted for Mills’ future and their desires for a possibility of a partnership with UC Berkeley.

Amongst the surveyed members of the Mills Staff Union, 65% identified as “the sole breadwinner in their household” and 85% rely on health care benefits for themselves and/or their dependents.

“From the perspective of staff, and from the perspective of the workers at the college [there is] a level of sort of importance that these positions hold. So, folks are very worried about that,” Caetano said. “Also, in our survey, we knew it was going to be important to ask this because, you know, pay and benefits, all that stuff is important. But it’s really not what drives a lot of people to come work at Mills, what drives people to come work at Mills are the students and the culture and the mission, and the vision and the values.”

Over the years dealing with budget deficits, staff at Mills have felt that these financial strains have fallen on them. According to Caetano, all workers lost their retirement matching benefits at the start of the pandemic. Retirement matching is when an employer matches the amount the employee puts towards their retirement by a certain amount.

In the Mills Staff Union survey, it was clear that most of the members felt it was important to maintain Mills’ culture that has been created by staff, faculty and students.

“I think that there’s good intentions at the executive level of the college,” Caetano said. “And I think that without specific and concrete commitments to how those good intentions will be carried out it leaves key constituencies, staff and students, I’m sure also, and faculty concerned about the future.”

In February, the Adjunct Faculty Union surveyed its’ members and according to Professor David Buuck, Chief Steward of the union, “a vast majority” rely on Mills as their primary source of income and wanted a guarantee of future employment and clarity regarding partnering with another institution.

“Not just because of the wages, I want to make clear it’s also because of the commitment to a certain kind of educational vision,” Professor Buuck said. “And the uncertainty is always hard. But certainly made harder in the current climate, for higher education hiring … The cost of living in the Bay Area, a lot of staff and faculty have deep roots here, families can’t necessarily just up and leave town for a potential job elsewhere. And the higher ed market for humanities and higher ed is not great right now. So there’s a huge amount of anxiety of ‘What am I going to do’?”

The Adjunct Faculty Union shares similar concerns regarding job security, the futures of students, faculty and staff, and an expanded partnership with UC Berkeley. While nothing has been finalized between the university and Mills, the union has questions regarding support for students who want to complete their degree at Mills and those who want to transfer to a similar institution.

“It is unclear to me if students will want to become UC Berkeley students,” Professor Buuck said. “… UC Berkeley will most likely, if it works out, be taking over the campus and the buildings and having UC Berkeley classes and a presence on campus. So the question is, will Berkeley be hiring? Will there be employment opportunities for Mills faculty and staff in UC Berkeley, and that, increasingly appears that there will be no guarantees whatsoever for Mills, faculty or staff, to be employed by UC Berkeley.”

According to Professor Buuck, in the beginning, there was hope that UC Berkeley would hire tenured and tenure-track professors in the event that there was an acquisition of Mills. The adjunct faculty union had to put pressure on the administration to be offered a similar opportunity as tenured and tenure-track professors, who were being offered workshops to put together professional portfolios for hiring consideration at UC Berkeley.

“Providing a workshop on how to improve your CV and give good interviews is very different than ‘We will work to make sure that you are given two years commensurate salary and healthcare … as severance to weather the storm of unemployment as a result of this,” Professor Buuck said. “And now it seems like Berkeley is saying, ‘We are not going to guarantee … who we’re going to take, it’s going to depend on our needs, is going to depend on individual departments, etc.”

While there are many unanswered questions, Professor Buuck does not believe the administration is trying to hide information.

“I think it’s an unknown,” he said, “But that also means that’s a place where students and, and community members and alums can put some pressure to have some input in that.”

Students and alumni have begun to organize through a Facebook group and Slack channel called “Save Mills”, This Friday at 4 p.m., the organization has planned a rally at Richard’s Gate at Mills College. Members of the organization have continued to share information and create plans for a new future for Mills in order to reverse the Board of Trustee’s decision.