This article is the third part to a series about the immersive experience of the Mills students who traveled along the Arizona/Sonora border and the real issues that the families and children within these communities face. The writer of this piece was also involved in the trip and while opinions shared throughout the series may not represent The Campanil staff, we felt this was an important issue to report.

José Antonio Elena Rodríguez, a native of Nogales, Sonora, was a young teenager walking home from a basketball game when he was shot ten times—eight times in the back, twice in the head—and died at the scene. He was the victim of government-controlled violence; the bullets that hit him came from the gun of a border patrol agent.

According to The New York Times, on Oct. 12, 2012, a phone call was received by a police officer in Nogales, Arizona reporting “suspicious activity” on a road directly alongside the border. Nogales is the name of both cities in Arizona and Sonora that are divided by the border. When the officer, John Zuñiga, arrived at the scene, he was told by another officer present, Quinardo Garcia, that two men had climbed the fence into the United States with “large taped bundles to their backs.”

Based on the occurrence of drug smuggling across the border, Garcia identified the bundles as marijuana and called for backup. He then chased the two men but stopped as they disappeared into a nearby overgrown yard. Due to fears of an ambush, he waited for other officers to arrive.

Within minutes, several police officers and border patrol agents arrived and began searching for the men. They were spotted climbing the fence back into Mexico. Police officers and border patrol agents avoided climbing onto the fence for safety and jurisdiction reasons, so Zuñiga verbally commanded the men to climb down. At this point, officers reported “rocks flying through the air” and then hearing gunshots fired.

The shots were fired by border patrol agent Lonnie Swartz, who claimed he fired in self defense against the rocks being thrown at him by Rodríguez. He was brought to trial and charged with second-degree murder. A witness testified saying that Rodríguez had not been throwing rocks, although evidence showed he had been among other youth and men who were along the border during the incident. In April 2018, Swartz was found not guilty of second-degree murder. The jury was deadlocked on the lesser charges: negligent homicide and involuntary manslaughter, the lowest level of manslaughter.

“The case felt familiar in terms of the case of brutality,” Mills sophomore Ma’kaya Washington said. “As a Black person, I’m not really new to that kind of thing so [when] someone [is] killed by a federal officer [and] there is a lot of dispute about what happened, I don’t think that’s new to anyone who is a part of the community of Black and brown people being killed in cold blood.”

The Mills students participating in the Borderlands course were able to have a conversation with Luis Fernando Parra, the lawyer representing Rodríguez’s family, and learn more about the details of the trial. A civil and criminal case was filed against Swartz, although according to Parra the family’s fourth and fifth amendment rights were violated.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) refused to release surveillance-camera footage of the incident. The footage was meant to be used during the trial but the CBP’s defense had an information technology expert testify that the hard drive where the video was stored had been auctioned off or destroyed. The expert testified that there was a small clip retained from the hard drive but said it was distorted, therefore unusable. The CBP defense continuously argued against the use of the clip during the trial and a decision was made for it not to be included in the evidence. The family’s preservation letter for the video was ignored by the federal government.

Peg Bowden, a humanitarian activist and author, said that she had seen the video and felt that it was not grainy nor distorted. The government has not released the video to the public. Parra, a fourth generation border resident, discussed how these kind of decisions have important ramifications on border cities and communities and contribute to how they are marginalized. He believes that CBP destroyed the video and got rid of other related evidence.

The CBP’s defense argued that the case should have been thrown out because of Swartz’s qualified immunity and the fact that the victim died in Mexico, therefore outside of their jurisdiction. Although the United States has operational control of the border, there is a sixty foot marker of land from the border that belongs to both countries. Cases that occur within those areas are meant to be handled diplomatically.

James Tomsheck, former chief of Internal Affairs with CBP and U.S. attorney, filed a claim under the Whistleblower Protection Act and advocated for an investigation of border patrol brutality. This was not the first time Swartz had been involved with violence. He had a history of going AWOL from the military and the students learned from Parra that nine months before the shooting Swartz profiled and arrested a resident in Nogales, Arizona.

A student who attended Nogales High school was driving into Patagonia, Arizona when Swartz began to follow them. He then pulled her over at a gas station and questioned why she didn’t pull over when she saw the police car. She responded in Spanish, although she spoke English, and Swartz demanded her to get out of the car. As the student was exiting the car, Swartz reportedly grabbed her and threw her against the car. Her keys were in her hand attached to a lanyard and in the police report, he reported that she attacked him with it. The student was arrested along with her friend who was also in the car and was questioning why the agent was arresting her.

The student was taken into custody and was not allowed to call her parents for an entire day. She was prosecuted for assaulting an officer but was found not guilty. Her family tried to file a civil case against Swartz but was unable to because of how long her case took to appear before a judge. A civil case can only be filed up to two years after the incident has happened.

The border patrol has a history of violence against marginalized communities and Tomsheck accused the agency of covering up shootings and corruption.

People protested the killing of Rodríguez but protests began a year after his death. This was mostly because of how information was withheld from the public. Every year on the same day of the killing, a demonstration is held and a ceremony is performed at his burial site.

The case inspired many local citizens of Nogales to become more involved with activism when understanding better how people are abused in the custody of U.S. Customs and Border Protection and processed through Operation Streamline, which was previously reported on in The Campanil.

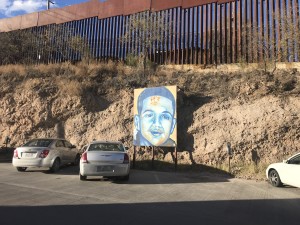

While border patrol is not legally allowed to interrogate an individual based on their race and ethnicity, there have been instances where people have gone to court against CBP to accuse an agent of racial profiling. Murals are spread throughout central Nogales, Sonora where artists have created images that express the harsh realities of families needing to cross the border and negative sentiment towards the existence and heavy security of the border.