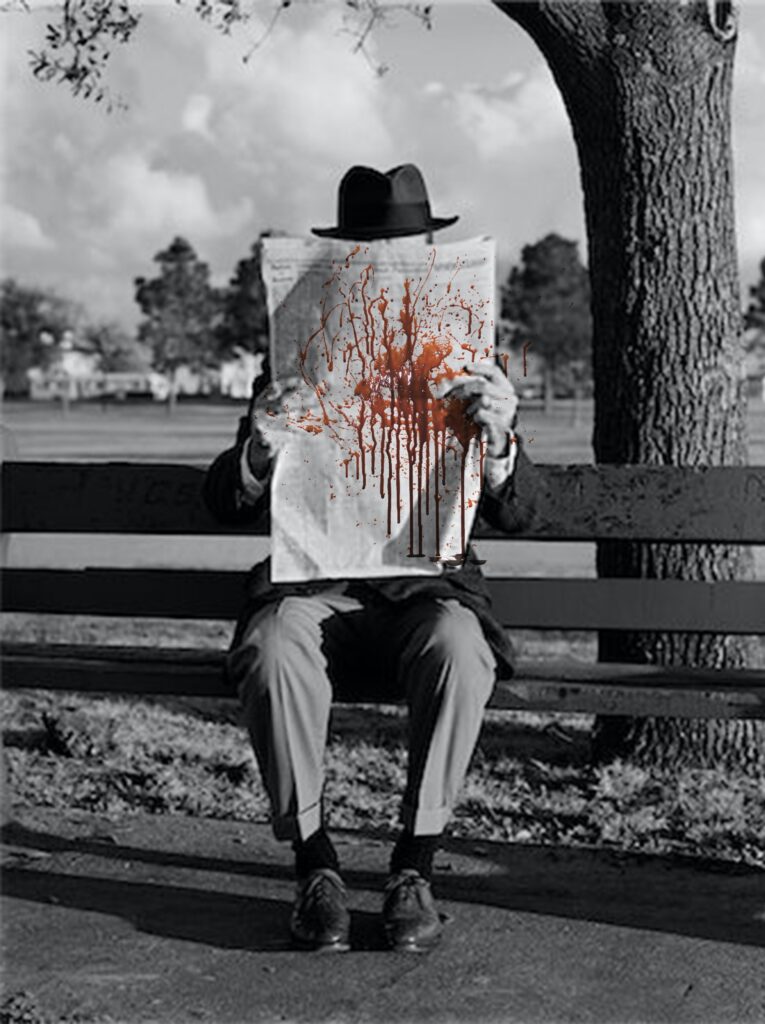

Just like the rest of America, I watched HBO’s retelling of Dylan Farrow’s and Woody Allen’s trial by media, “Allen V. Farrow.” And, like most of America, I didn’t find anything remarkable in it. It was without a doubt powerful and moving to see adult Farrow telling the story from her perspective, uncensored and verbatim in all its horror, but “Allen V. Farrow” still doesn’t deviate hugely from your average true-crime schlock; somber music, grainy vintage footage, salacious voiceovers, and although it has no narration, it has enough predatory monologues from Allen to make up for it. So all that in mind, it’s no surprise that “Allen V. Farrow” didn’t remain in my head much until it went out the other ear, at least not until I saw a few odd editorials that stuck out from the mostly glowing reviews that asked important questions: who is “Allen V. Farrow” helping? Is it exploitative? Is that exploitation somehow worth it?

These are questions that are relevant to all journalism, crime journalism especially, so as the staff of the Campanil we sat down to try and answer some questions of our own. I told my colleagues what I had watched and read, and I asked them: as consumers, potential true crime fans and as journalists, how can we cover sensitive and sensational subjects without exploiting them?

As writers for the Campanil, we believe that it is our moral imperative as journalists to avoid the exploitation of the subject by covering them in a way where they receive a direct benefit when appropriate. We also believe that one of the best ways to understand the function and practice of exploitative journalism is to look at the true-crime genre; while it’s not commonly covered in the Campanil, there’s no shortage of coverage elsewhere online, its quality ranging from respectful investigative journalism to shock-jockeying clickbait. (See: “The Thin Blue” line as opposed to the Oxygen network.)

In the last few years, activists have over and over cried “representation!” as a way to ensure the favorable portrayal of various minority groups in the media; people call for LGBTQ creators to create LGBTQ media, people call for Black stories to be told by Black writers. But the reason this kind of behind-the-scenes representation is important not just for its inherent values, but for the way it ensures the creation of content about a certain subject made by the subject themselves. The best way to ensure a subject’s sensitive portrayal is to make sure that they have control over their own narrative to the largest degree possible. This is crucial in humanizing peoples’ stories and minimizing outgroup bias. When a piece or an outlet is publicly criticized for some sort of insensitivity, it usually follows that the senior administration is full of rich, white men. It comes as no surprise that journalists are advocating for more people of color in newsrooms, especially when it comes to their own stories.

So what about “Allen V. Farrow”? Is its coverage of Dylan Farrow’s abuse to her own benefit? Well, it is easy to understand why there’s debate. The documentary capitalizes on what most true crime rehashes of old media trials do: never before seen footage! In the case of “Allen V. Farrow,” the footage is

Of course, this analysis can and does expand beyond the true crime genre. Another important nexus of potential exploitation is coverage of marginalized groups in general. The New York Times’ 2018 piece, “Trapped in Walmart of Heroin” by Jennifer Percy is a great example of how even prestige journalism can be exploitative. The piece is largely about Kensington mayor Jim Kenney’s efforts to alleviate his city’s dependence on opioids and heroin, but that municipal tale is strung atop a scaffold of human suffering in order to add gravitas to the situation. The subjects Percy interviews aren’t treated with empathy and they certainly aren’t meant to be understood.

There’s Elvis, who “lives on a small, crumbling block next to a demolished crack house,” there’s Jax, a sex worker who “had smoked crack and scratched up her face. It was speckled with wounds,” and Kevin, the “short man with a wild beard. Opioids often make people itch, and Kevin wouldn’t stop scratching his arms. There was so much dead skin it looked as if his arm were foaming.”

Much of the story is spent detailing the geography of the city as shaped by its addicts, and it does not mince words. There’s an extended picture of tragedy that Percy paints of addicts who are squatting at a nearby church. These people aren’t named or interviewed or compensated, they’re just part of the periphery of “the needles in the holy-water basin,” the shocking sight that Percy wants to emphasize. And that’s just a few examples. One sob story after another, exploitative in that it doesn’t serve its subjects and that their stories are unquestionably taken advantage of to report on the Mayor’s agenda to forcibly remove a vulnerable population from their home and into treatment.