I spend my days thinking about dead people. In other, less morbid words, I am a history major with a genealogy craze. One of my favorite things to do is read old yearbooks. I’m happiest at the library, poring over the adventures of past Millsies. I knew that I wanted to write an article related to the history of Mills for this issue, but I didn’t initially think I’d write about the yearbooks. I didn’t think my relief that pantaloons are no longer in style was a sentiment worth publishing (although I suppose it has now been published). That was before I found the Mills College Junior yearbook of 1921.

In 1921, the editor(s) of the Mills yearbook decided that a yearbook saturated with photos (which were, to be fair, much more difficult to obtain than they are today) was not their artistic vision. They wanted student writing — and a lot of it. A glance at the table of contents reveals that student literature filled about a third of the yearbook; 50 pages, to be precise. That literature consists of poems, short stories and even jokes. Given Mills’ small size, I wonder if the editors rolled with any and all writing that was submitted, and I adore that. “This is the essence of Mills,” I thought to myself. “This beautiful, oddball collection of writing could not encapsulate Mills more.”

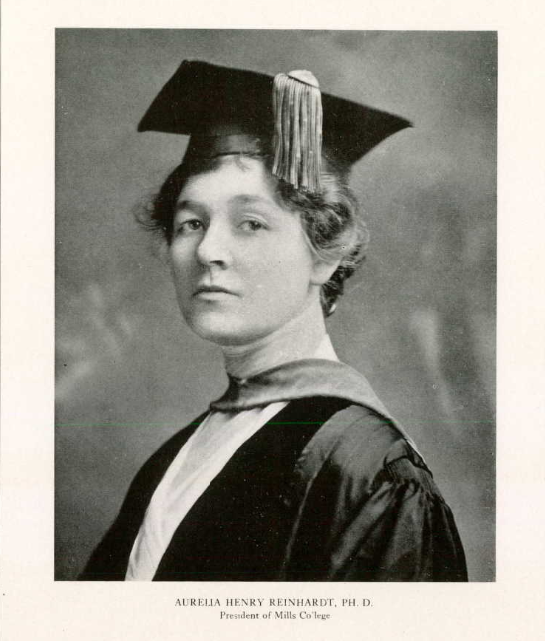

The yearbook’s statuesque opening picture of then-president of Mills, Aurelia Henry Reinhardt (who was a fascinating lady), does not foretell the levity to come. Reinhardt’s story is a powerful one; she obtained a Ph.D. as a woman in the 1920s and raised two children alone after the death of her husband. In fact, the yearbook editors dedicated the yearbook to her two sons and the joyful energy they brought to campus.

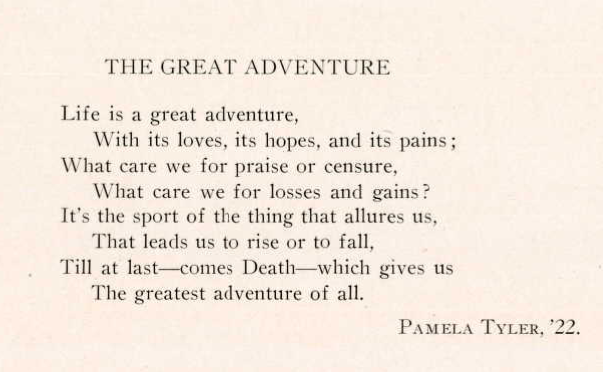

Pamela Tyler, class of 1922, actually wrote of the Millsie adventures I mentioned in my first paragraph. Underneath her poem, she wrote, “The idea that prompted me to write this was the last words of the admirable theatrical manager Charles Frohman, as he was facing death on the ill-fated ‘Titanic,’ at which time he remarked ‘What is death — it is only the big adventure.'”

I am both moved and impressed by Tyler’s poetic response to the tragedy of the Titanic. When I watched the feature film with Leonardo DiCaprio, all I did was sob for three hours.

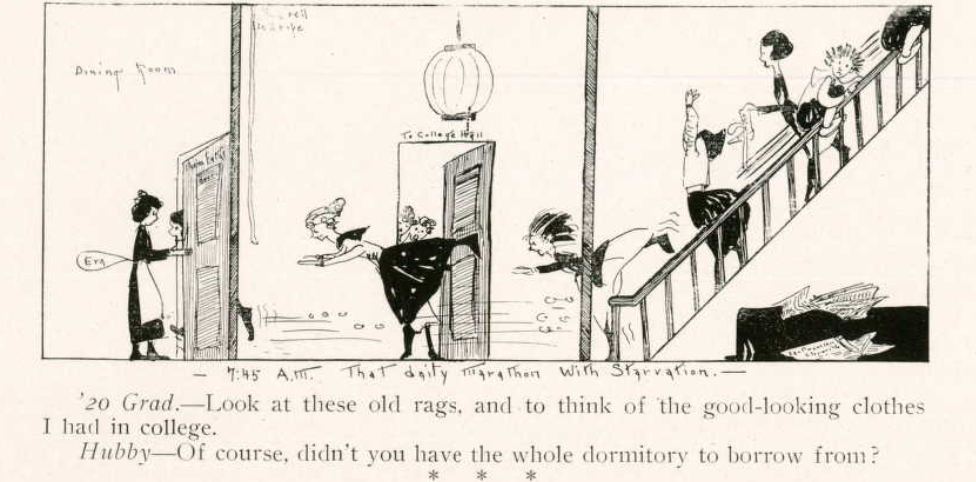

The beauty of the 1921 yearbook is that, 100 years later, each joke and work of writing is somehow relevant to Millsies today. Instead of sharing fine dresses and ruffled collars, as depicted in the comic strip below, we share hair dye and homemade crop tops (my friends have given me a few I cherish, but can’t lift my arms up in without risking indecency). I believe having at least one drastic hairstyle change is part of the modern Mills culture, although it would be nice if the showers didn’t look like a crime scene after somebody gives themselves a mullet and dyes their hair red.

After mentioning the shower fiasco, it might be a good time to include something with calming energy. This is a lovely poem about a fir tree, and I very much enjoy it. Ruth Ferguson, class of 1923, was ahead of her time in writing “Fir tree, you send a challenge to us, But we pass it by, for we think we must.” Care for and appreciation of the natural world in a time of industry is still a hugely relevant topic today.

Margaret Sloss, class of 1921, echoes a similar sentiment to Ferguson. Millsies have been lovers of nature and critical of consumerism for a century … or so I hope!

“The Things That Other Women Build” by Lois Hunter, class of 1921, spoke to me more than anything in this yearbook (even the above comic strip). Sometimes I think the things I’m building here at Mills “break within my hands,” but I know that with the strength and love of this supportive community (which includes not only women, but men, nonbinary people and people of other gender identities), I will come to “find my work both true and clean.”

And finally: it is not lost on me that Esther Butters, class of 1921, named the main character of her short story An Elderly Romance “Mrs. Gay.”

Jokes aside, my fondness for Mills grows each day. It is difficult to look at Mills’ history uncritically, as the student body in the 1920s was overwhelmingly white and, likely, wealthy. This fact is paramount to acknowledge, and my delight in journeying through the writing in this yearbook is coupled with the sober knowledge that homogeny and privilege were a huge part of Mills for some time. Mills has changed greatly over the years — in my opinion, for the better. Whoever the Millsies of 1921 were, I was glad to sit down and listen to them for a few hours. I will seldom turn down a chance to sit and listen to a Millsie, for the essence of Mills is the lively and clever spirit of its people. I will carry Mills’ history, from its founding to my time here, in my heart forever, with much gratitude.