Oakland, CA – On April 3, 2022, Chief News Editor Tasha Poullard of The Campanil sat down with a Haitian national, “Jean” (name changed for privacy), to hear his thoughts on the disenfranchisement of Haitians who have fallen victim to misappropriation of relief aid, government corruption and gang violence in their country.

While the U.S. weighs the option of assisting Ukraine’s resistance to the Russian invasion, the images of Haitian immigrants being beaten with whips at the Texas border are still fresh in the minds of many Americans.

Special Representative for the United Nations’ Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH) Helen La Lime briefed the United Nations Security Council on the need for increased structural organization in Haiti on February 18, 2022. La Lime addressed the need to curtail the rise in gang violence and the importance of closing loopholes of impunity for violent human rights abuses. Thousands of Haitians have been executed, tortured, raped or endured arbitrary detention by Haitian troops and gang leaders.

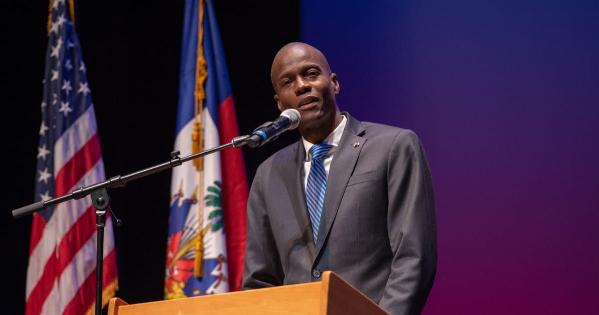

In addition, La Lime emphasized the imperatives of eradicating government corruption and providing sustainability to the nation’s economy. She claimed that bringing stability to the country following the assassination of late President Jovenel Moïse is of utmost importance.

According to Human Rights Watch, a combination of the COVID-19 pandemic, a prolonged economic crisis, the assassination of President Moïse in July of 2021 and multiple large-scale earthquakes have “exacerbated Haiti’s existing challenges of political instability and violence by gangs often tied to state actors.”

Foreign Affairs reports the country is now governed by its prime minister, Ariel Henry, who many Haitians feels lacks legitimacy, and has made very little progress in restoring order.

In his interview with The Campanil, Haitian national “Jean” gave his thoughts on the state of the nation in peril, and how Haiti has continuously struggled to meet the basic needs of its people.

In April of 2010, before the earthquake, Jean was working as a fleet dispatcher in Haiti. His job was to transport crisis workers to and from their destinations on the ground while assessing the damages following natural disasters. He worked with nonprofits such as World Vision International and Save the Children for two years.

Jean had the privilege of working closely with government officials and wealthy business men, allowing him to witness the mishandling of relief aid firsthand, alongside the crumbling of his country’s already-fragile foundation following President Moïse’s assassination. When reflecting upon the literal breakdown of the country following the large-scale earthquake that occurred in January 2010, Jean stated that he saw his country take a turn for the worse.

Photographer: Ralph Tedy Erol / Reuters

In a mix of English and Creole French, Jean explained with the help of an interpreter that there was little positive change following the millions of dollars in aid given to Haiti by the international community. Haitians are still grappling with food insecurities, lack of housing, government and gang violence.

“If I want to talk about the percentage [of people who received assistance] I can say about 25% of the people got help,” Jean said. “They get the U.S. aid, in cash, and don’t do exactly what they promised.”

Global News reports the global response to Haitian aid totaled $13.5 to $16.3 billion. The U.S. pledged support for rebuilding and recovery efforts following the earthquake, and the Canadian government donated an estimated $220 million to $1.458 billion, which does not include the $220 donated by Canadian citizens. The American Red Cross failed to demonstrate where millions in donations had gone after having raised half a billion dollars in one of the most successful fundraising efforts ever. In 2014, there were still 400,000 or more Haitians living in tents and makeshift shacks following the 2010 earthquake, according to Reliefweb.com. In June 2015, the American Red Cross made claims of constructing housing for more than 130,000 people — while the number of permanent homes the charity built was reported to be a total of six.

To investigate where these donations ended up, NPR and ProPublica reviewed hundreds of the charity’s confidential documents and emails and uncovered mismanaged projects, suspicious spending practices and false claims of success. Presently, the Red Cross still has not successfully produced housing or sanitation solutions (such as public bathrooms, clean running water or safe living conditions) to displaced Haitians.

According to Disaster Philanthropy, an estimated 217,000 children were reported to suffer from moderate-to-severe acute malnutrition in November 2021. With the ongoing political crisis, socio-economic disenfranchisement, and food insecurities worsening, an estimated 4.4 million people (nearly 46% of the population) are facing acute food insecurities.

According to The New Humanitarian, the surge in gang violence and deadly kidnappings has slowed down the shipping and receipt of goods, food and medical supplies, causing nonprofits to rethink shipment routes in order to keep staff safe. The food shortage is leading to an increase in gang violence. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) estimates that more than half of the Haitians who need humanitarian assistance, roughly 2.5 million of the country’s 11.4 million inhabitants, currently live under the control of armed groups called Baz, as they are called in Creole. Baz have traditionally served as armed defenders of the interests of those with power or wealth.

“We don’t have gun shops in Haiti. All the guns [the gangs] used are illegal,” Jean said. “They ship them in from the Dominican Republic, Jamaica and Miami; most of them are from the United States. When the Brazilian Minister came to Haiti [following the earthquake], I cannot say for sure, but I believe they sold guns to some of the Haitian people.”

InSight Crime reports that, as the world’s largest firearm supplier, the United States is a major source of illegal weapons smuggled into Haiti. Many of the gangs currently in Haiti are from the United States and the Dominican Republic, who utilize cargo shipping containers to smuggle guns into the nation and hold kidnapped individuals hostage. Haitian law enforcement are both corrupt and few in numbers. Jean says that for a population of nearly 12 million people, there are only 15,000 police officers. In 2021, notorious leader of the gang alliance known as G9 and former police officer, Jimmy “Barbecue” Chérizier, successfully blocked the distribution of oil, demanding the ousting of Prime Minister Henry.

There is no Haitian military to stop the flow of guns, drugs and gang violence. The gangs often offer their services to politicians running for office, blogging polling stations, removing voting ballots or incorporating voter intimidation with violence, to ensure corrupt officials are elected into political office.

Jean’s sentiments are reflected by Foreign Affairs‘ report that Haiti has a “broken political system and the deep connections between politicians and criminals.” The international relation magazines claims that the late president Moïse’s tenure was “marred by massive corruption, authoritarian leanings, and alliances with unsavory criminal forces,” and that Haiti’s political dysfunction has given way to a criminal takeover of the country’s governance.