David Rosenboom, composer, researcher and former director of the Center for Contemporary Music at Mills, kicked off a new series of lectures on Jan. 28 with a talk on his work in experimental music and neurofeedback.

The Mary L. and Tony Bianco lectures, scheduled throughout the Spring 2016 semester, are being put on by the music and history departments to promote interdisciplinary education for students within the departments. Rosenboom, a former Mills professor from 1979 to 1990, who has made a career out of boundary crossing and combining disciplines through his study of natural, biological and mathematical systems as models for music, was a fitting first guest for the program.

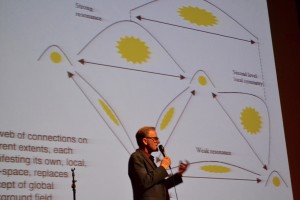

Rosenboom’s lecture was as multifaceted as it was comprehensive, covering topics from neuroscience to self-organizing musical universes. But his enthusiasm and breadth of knowledge comes as no surprise to those who know him and follow his work.

“He’s a big idea person,” David Bernstein, head of the Mills Music Department said of Rosenboom. “And his big ideas range from the philosophical to the scientific to the artistic. He has these grandiose ideas and he realizes them musically.”

Rosenboom has been studying neurofeedback in music for as long as the discipline has existed, even working with John Lennon and Yoko Ono in the early 70s on experimental music involving the reading of alpha brain waves. Harmonic collisions between art and science have defined his career: Investigating how musicians interact with their own music, and how that music interacts with the world around us has always been far more compelling to him than performing the classics. For Rosenboom, music has never been something to be passively practiced and plainly recited; it is something movable and changeable with a life of its own.

“Sometimes I look at a piano and I say ‘What good is an instrument if I hit this key and I always get an F sharp? I’d like to get something that I can’t predict!’” Rosenboom said during the lecture.

Though a virtuoso player of several instruments in his own right, Rosenboom finds music much more interesting when pushed to its limits through technological and biological intervention. Occasionally, this even meant designing his own instruments, including an analog keyboard played in conjunction with Lennon and Ono’s brain waves, and collaborating with Don Buchla in the 1960s on the earliest synthesizers.

During his time as a professor at Mills, he developed his own computer programming language called the Hierarchical Music Specification Language (HMSL), which allowed musicians to compose pieces with algorithms and mathematical models. Though HMSL has become obsolete in the decades since its creation, Rosenboom continues to use algorithms and models to create interactive music.

“People say to me sometimes: ‘Why do you work with model building in composition?’ And one of the reasons is that…it leads me into things I wouldn’t have discovered if I was following my habits in composing,” Rosenboom said.

Chris Brown, who now holds Rosenboom’s old position as director for the Center of Contemporary Music, recalls studying with Rosenboom as a grad student.

“It was very exciting, but it was also somewhat bewildering,” Brown said. “David’s ideas go very far in many directions at the same time, so sometimes it was a struggle to keep up with him…but [he’s] visionary that way. It’s like he’s pushing forward, trying to get to a full understanding of the potential of changes in technology and changes in our consciousness.”

Rosenboom has been working for years with advanced biofeedback technology, and only in recent decades have many of his early ideas been technologically possible. In May 2015, Rosenboom collaborated with UC San Diego music faculty to realize some of his earliest aspirations of full-brain mapping in live music, creating a piece called “Ringing Minds” for the Whitney Museum of American Art. Rosenboom continues his investigations to this day at CalArts, where he is a dean and coordinator for the music department.