FRESNO, Calif. (KGPE) — On January 29, 2020, an English assignment at Roosevelt High School that was presented as an African-American language explainer sparked outrage from students, parents and community members. The students were required to translate the misspelled language and bad grammar of so-called “flawed” or improper English, complete with grammatically incorrect sentences and African American Vernacular English (AAVE) or Ebonics.

Many people attended an emotionally charged press conference, taking their turns voicing strong disapproval of the assignment to the school board. The school district responded with a written apology, confirming that the worksheet is not part of the district’s official curriculum.

The history of what is considered “black vernacular” is rooted in the history of systematic oppression and racism against African Americans. These views of Black education are often associated with grammatically incorrect language like “double negatives”, or verbs that don’t agree with their subjects. These discriminatory views of Black communication cause many in society to constantly check the grammar, spelling, writing and speech patterns of Black Americans.

“I’ve been challenged many times about my resume and my training – because of my blackness and my youth. I get questions like ‘Oh, so what did you learn there? What did you do?’ Condescending shit like that to ‘confirm’ if I’ve actually done and know what I’ve been taught,” Alric Davis, a Black playwright, producer, director and Howard graduate, says.

Mills student Alexis Coleman says, “My mother grew up in Louisiana. She knew and understood the challenges we would face as black students in education. So she would write the correct pronunciation and proper spelling for household items on note cards, taping them to the items surface. My siblings and I would then read the cards, giving the correct way to say the words and spell out the words. She had taken the extra steps to make sure we were ready for school.”

African Americans are constantly reminded that we do not speak, read or write “proper” English. This is called linguistic prejudice, as described by a professor of psychology at the University of Chicago, Katherine D. Kinzler, in her book “How You Say It: Why We Judge Others by the Way They Talk — and the Costs of This Hidden Bias.” Kinzler explains that how we view others is affected by such factors as race, class and gender, which shape our social identities, and thus who we perceive as “like us” or “not like us.”

We often overlook how we perceive people based upon their speech patterns — how they pronounce words, even how they formulate sentences. The socialized factor of how people speak is linked to our social identity. Kinzler explains that “our speech largely reflects the voices we heard as children. We can change how we speak to some extent, whether by ‘code-switching’ between dialects or by learning a new language; over time, our speech even changes to reflect our evolving social identity and aspirations.”

The racially insensitive approach of demanding people speak and only teaching “proper” English, or even mocking AAVE, is built upon a myth of Black inferiority and intellectual incapacity. It is also historically rooted in Black enslavement.

Literacy for Black slaves had the power to threaten the economic growth of slave states, where slaves were dependent upon their white slave masters for survival. Whites in many colonies instituted laws forbidding slaves to learn to read or write, even making it a crime for others to teach them. When Congress began to abandon the promise to assist disenfranchised Black people following the Civil War, violence erupted and mass lynchings were carried out in hostility towards African Americans — especially African Americans who knew their Constitutional rights and freedoms, and who could read and write.

African Americans living in former slave states knew that education was vital to achieving equality, independence and prosperity. Many of them found ways to educate themselves despite the obstacles that living in poverty, and white people, placed in the way of progress. The overwhelming demand to find qualified teachers and build school houses made education difficult for African Americans. Prior to the Civil War, there was no educational structure in place for Black slaves. Education for African Americans was inaccessible as a result of public policy and various statutory provisions that prohibited the education of African Americans, mostly in the Southern states.

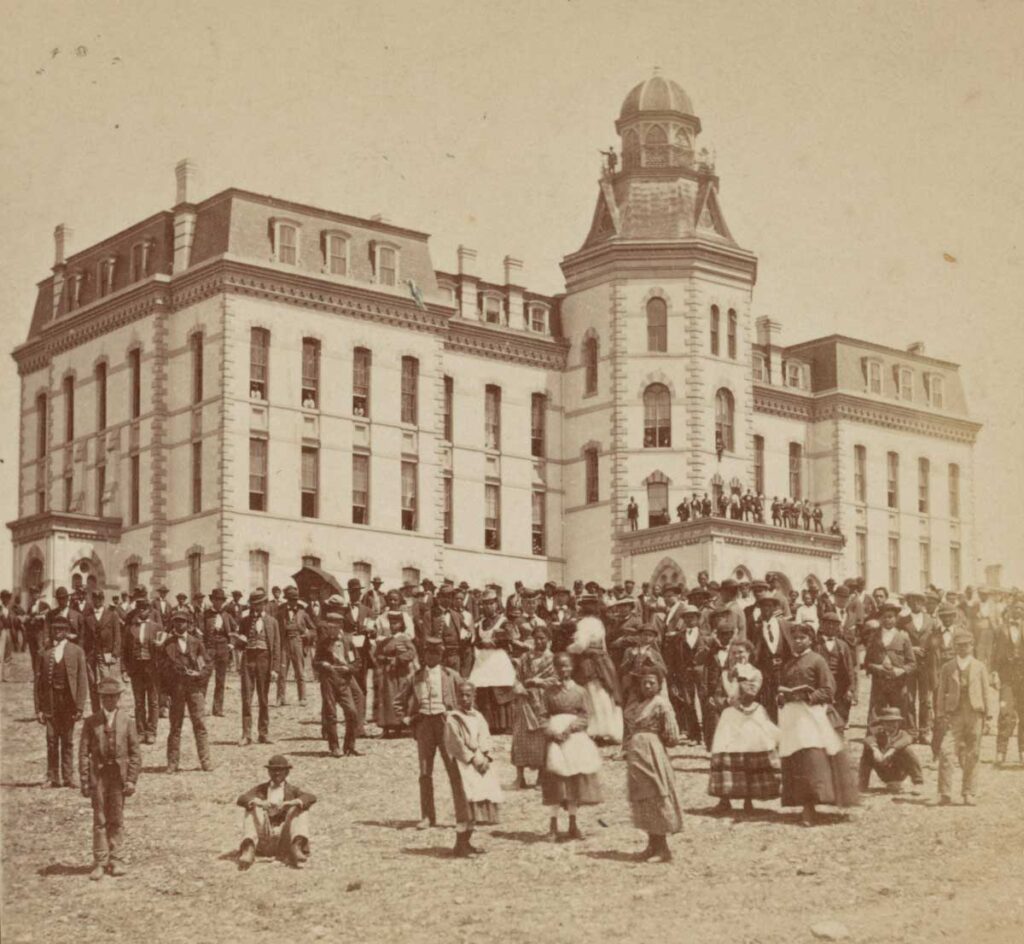

It was difficult and often dangerous for African Americans to acquire land to build school houses on and find the funding to pay teachers. When they were being denied admission to predominantly white institutions (PWIs), they turned back to the government and their own institutions for assistance. Thus, Historically Black Colleges (HBCUs) were formed, institutions of higher learning created to “serve the educational needs of Black Americans,” which became the principal means for providing post-secondary education to those who graduated from grade school.

Library of Congress

The Institute for Colored Youth was the first higher education institution for African Americans; it was founded in Cheyney, Pennsylvania in 1837. It was soon followed by two other Black institutions called Lincoln University, established in Pennsylvania in 1854, and Wilberforce University, founded in Ohio in 1856. Soon after the nation’s first HBCUs — Howard University in Washington, D.C., and Fisk University in Tennessee — opened their doors for business.

But this newfound liberation was not celebrated for long. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, between 1865 and 1877, thousands of Black women, men and children were murdered, severely beaten, sexually assaulted and terrorized by white mobs who never faced arrest and prosecution. White perpetrators carried out random acts of violence against freed Black people as a means of keeping them in the bondage of illiteracy and servitude.

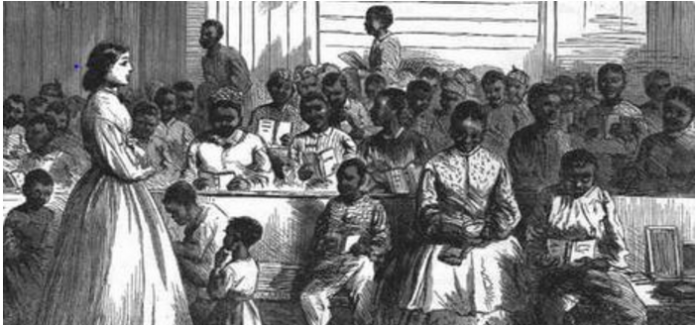

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, was established by the War Department by an act introduced March 3, 1865 (extended twice by acts on July 16, 1866, and July 6, 1868) with the hopes of providing relief to freed slaves. The Freedmen’s Bureau was responsible for supervising and managing all matters relating to the freed African Americans, who were considered “refugees.” The major function of this bureau was to provide the much-needed relief that would help formerly enslaved people become self-sufficient. Their primary concern was the establishment of schools for freed slaves. Educational support was vital to newly freed peoples’ survival because they could not read or write. By 1868, schools for Black children became a priority, and there was a surge in Black leaders winning elections to public office.

The Bureau was welcomed by newly freed slaves, but faced resistance from white Southerners and President Andrew Johnson, a poor and uneducated white man who believed the U.S. Constitution guaranteed white Americans the right to own slaves. Once in office, Johnson worked diligently to restore the Southern states to the Union, granting amnesty mostly to former ex-Confederate officials that he appointed to political office. These new appointees enacted what were called Black codes, or “restrictive laws designed to limit the freedom of African Americans and ensure their availability as a cheap labor force after slavery was abolished during the Civil War.”

To mock Ebonics or black English vernacular, simply because someone does not spell, read or write according to how whites interpret the English language, is a form of racism called a racial micro-aggression, a term first proposed by psychiatrist Chester M. Pierce, MD, in the 1970s. It refers to daily verbal, behavioral or environmental messages that communicate harmful slights and insults about people of color. Whether intentional or unintentional, racial micro-aggressions shame racial/ethnic minorities and perpetuate racism. It is racist when speaking, reading and writing “good English” is seen as synonymous with being acceptable to whiteness and confined to a master/slave concept of canonized education. Whites who correct Black vernacular place themselves in a position of “master” ownership over the “slaves” they correct. This is a racist dynamic that links the human worth, rights and dignity of an African American to their “proper” use of the English language.