I was 24 years old when I started experiencing chest pains one morning. I fell to my knees on my living room floor, drenched in a pool of sweat, overcome with fear. At that time I was a Third Class Petty Officer in the U.S. Navy working in cyber security at Ft. George G. Meade. Everything I did was under a microscope, and I needed to be very careful about how I conducted myself. So I couldn’t tell

anyone what happened to me. I had just suffered what I later learned was a panic attack.

At that very moment, I heard a voice in my head say “You’re going to get in trouble for something at work and lose your clearance.” I froze as I saw visions of myself being stripped of my rank, having my clearance revoked and receiving a dishonorable discharge from the Navy. I was so overcome with emotion that I couldn’t move past my front door. I was an hour and thirty minutes late to work and I ended up in what is called a disciplinary review board (DRB).

Prior to this event, I did not think that I had any issues with mental illness. I didn’t even talk about it with family or friends as a result of the stigmas associated with this topic in the black community. As a child, I always knew that I was sad, struggling with thoughts of taking my own life because I felt worthless. I felt as if nothing I did was ever good enough, as if I wasn’t good enough. This episode caused me to reflect upon a family member of mine who checks themself into a mental clinic regularly. The family has always believed they were doing this to get “crazy checks,” which was my family’s code name for government subsidies for mental illness from the state. It wasn’t until I chose to start seeing a mental health specialist that I realized this family member, whom I had poked fun at on occasion as well, was actually smart. They realized they had a problem, and were taking the necessary steps to find solutions, regardless of what everyone else had to say about it.

The mental health of black Americans is a topic that is usually only vaguely discussed. Such stressors as racism and discrimination are often compounded by a family history of mental instablity.

According to The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, violent acts that are highly publicized and depicted as anti-black may harm the mental health of particularly black Americans. The PNAS identified 49 incidents of targeted racial violence in the U.S. between 2013 and 2017, resulting in black Americans reporting poorer mental health in the weeks that followed two incidents of anti-black violence that were broadcast on public media platforms. Reducing such racial violence as police shootings involving black Americans is beneficial in reducing the mental stress suffered by black Americans.

There are an astounding number of black children who are raised in unstable environments, where mental health isn’t a priority. These children later grow into adulthood suffering from the same forms of mental deficiencies as their parents and are apprehensive about seeking treatment.

As black Americans, we experience a myriad of misconceptions about mental health as it pertains to the psychological stability of our community. Some of the reasons many black Americans are reluctant to seek mental health care include the fear of being called insane or labeled crazy, and avoiding the side effects of medication, among other contributing factors to this mental epidemic that include:

Inadequate and insufficient data on African American diagnosis: The lack of knowledge and professionally trained clinicians to treat depression in the black community has not been adequately addressed. This deficiency in research data, combined with a lack in certified specialists, contributes to the problems of under- and misdiagnosis, mistreatment and inadequate care of black patients believed to be suffering from depression.

As specified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, major depressive disorder (MDD) is the fourth leading cause of disability and a leading cause of non-fatal disease burden. It affects one in five persons in the U.S. with symptoms that are “physiological, emotional, motivational, behavioral, and cognitive” as specified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. A survey conducted found that black Americans have “lower lifetime rates of MDD.”

Additionally, the Medical Apartheid is contributing to a lack of mental health care. According to the Center for American Progress, it was reported that in 2018, 8.7 percent of black American adults had access to mental health services, in comparison to 18.6 percent of non-Hispanic white adults. Of that 8.7 percent, 3.8 percent of black American adults reported experiencing severe psychological distress. In 2020, an estimated 6.2 percent of black American adults received prescription medication for mental health support, while 15.3 percent of non-Hispanic white adults received prescription medication to deal with mental health.

These alarming statistics led me to research what exactly are we doing to assist our black students at Mills College in dealing with depression and mental illness. I had the pleasure of speaking to the founder and supervisor of the Black Mental Health Internship at Mills College, who would like to be referred to as “CAPS”. As per the Mills website, the Black Mental Health Internship at Mills (BMHI) was founded in 2019, with the purpose of addressing these [medical] disparities both on Mills campus and within the Bay Area.

BMHI is working diligently to create “accessible mental health services for Black communities by providing early intervention mentorship, education and training to Black students interested in a career in mental healthcare.” The internship’s overall design is strategically crafted to influence various ecological systems impacting Black communities’ wellbeing.” I wanted to know more about BMHI and how they assist black students at Mills with mental wellness.

Poullard: As per the Mills website, “Black Americans encounter a complex and ineffective system of mental healthcare, ranging from lack of access to services due to the cost of care, stigma, misdiagnoses, and anti-Black racism in various pipeline systems.” What are some of the biggest concerns that black Mills students have expressed that they need some level of mental relief from while attending your sessions?

CAPS: Racial trauma on campus and off, family trauma from childhood and boundaries with family members presently, lack of stable financial support and housing insecurity.

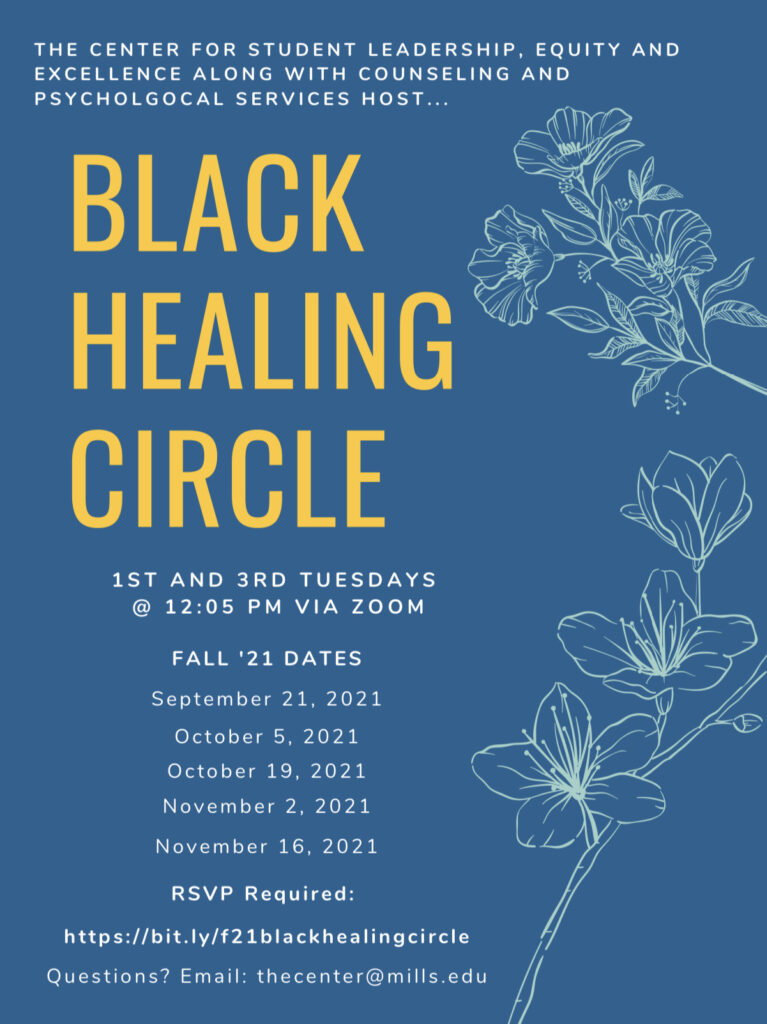

Poullard: I read that the Black Mental Health Internship at Mills (BMHI) was founded in 2019, and aims to address these [mental health] disparities within the Black community, what are some of the steps BMHI is taking to spread mental health awareness on Mills campus and attract more students to your sessions? What are some of the services provided to students who are seeking assistance that extends beyond the Black Healing Circle?

CAPS: We facilitate Black Wellness Workshops on topics that the Black students on campus have requested. The previous workshop topics are listed on that website as well.

Poullard: Why are you passionate about the mental health of the Black community, especially our Black students at Mills?

CAPS: I am passionate about the field and young adult Black women in particular because I had a very challenging time as a young Black woman with unstable housing, and a lack of financial and family support as I was trying to navigate and felt very isolated in a PWI at UC Berkeley. There was no support when I was a student. Black students had no Black therapists at their CAPS center on campus and I was referred off campus to white therapists who could not relate to my experiences. I wanted to be, for others, the person I needed to get through college.

Poullard: Can you give an example of one of the worst cases you’ve seen on Mills campus and what assistance was that student provided through BMHI?

CAPS: BMHI does not handle individual clinical work. This is a training program to prepare students for the field of mental healthcare. Only licensed professionals and clinical trainees can see clinical cases.

Poullard: What’s the overall goal of the BMHI for 2021, coming on the heels of some of the most heated protest and social unrest (example: the death of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, the January 6th insurrection) as we slowly open Mills back up to on-campus learning?

CAPS: Great question. The goal for BMHI in 2021 is the same goal for 2019, which is to increase the number of Black mental health professionals and to address mental health disparities facing the Black community by providing early intervention mentorship, education and training to Black students interested in a career in mental healthcare. There is a shortage of Black mental health professionals and lack of culturally-appropriate care. However, due to a lack of Black mentorship at the college level, potential Black mental health professionals choose other career paths. Additionally, Black students, especially Black women, assume the highest levels of student loan debt in the country, partly due to a lack of mentorship to avoid for-profit graduate institutions that target Black students. The outcome of this trajectory is a mental health professional with $400,000 in student loan debt who is forced to charge high private practice fees, leaving Black communities unable to access therapy services by Black mental health professionals.

In urban centers like San Francisco and Oakland, many Black therapists do not accept insurance because the reimbursement rates are too low for the high cost of living and high student loan debt payments. One aim of the internship is to provide educational, financial [and] career counseling, so that students will become mental health professionals with a low level of student loan debt.

Another goal of the initiative is to train aspiring Black mental health professionals to deliver culturally appropriate wellness services to Black college/university campus communities. These culturally appropriate services have taken the form of biweekly Black Healing Circles & 1x semester Black Wellness Workshops.

Poullard: Last question, are there any plans to potentially expand the services that the BMHI offers Mills Black students and the Black community in Oakland over all?

CAPS: Not at this time, but we are discussing expansion internally.