Is it money?

Is it living what we believe to be the American dream?

Has social media altered our ideas of what black love constitutes?

These are just some of the questions I have been asked by both men and women when giving my thoughts on the health of black love today.

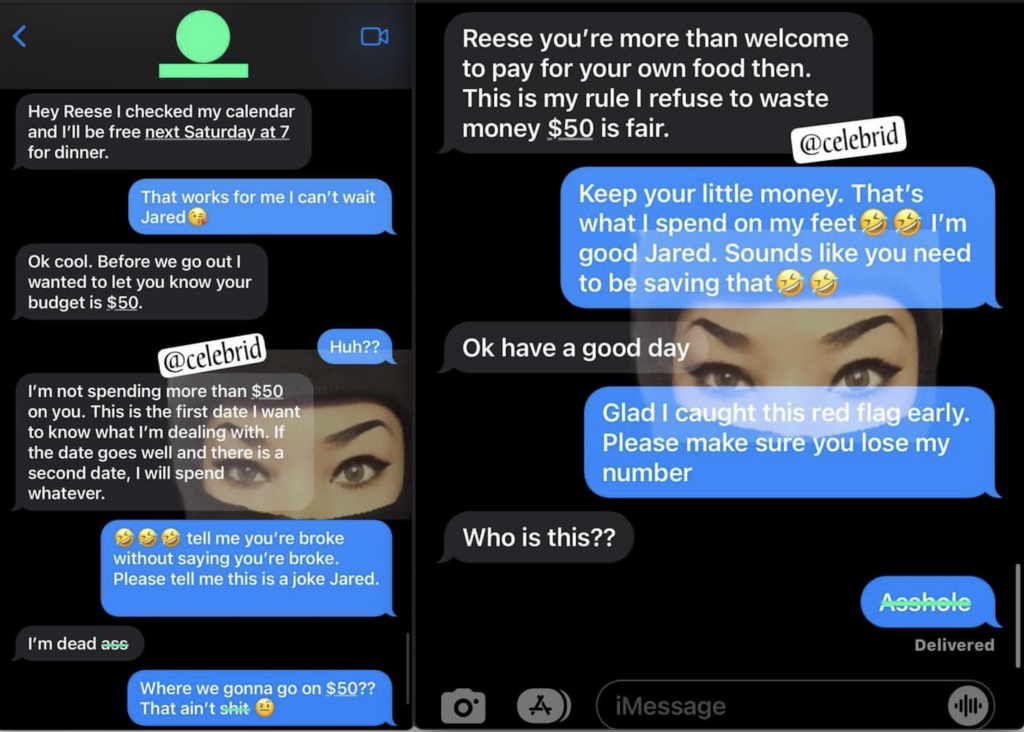

To illustrate, here’s a social media thread that was posted to Instagram by @celebrid titled “Budget Date.” Jared puts his future date, Reese, on a budget of $50, until he knows what he’s “dealing with.”

This entire thread sparked a debate about the change in relationship dynamics within the black community. I know the issue of money isn’t something that only rears its ugly head in the black community; it is universal. But it started me on a path of self–discovery.

When going out on dates, it is recommended that a woman have her own money. Women should plan accordingly, and have enough to pay for their own food and Lyft or Uber if drinking is involved.

In order to avoid such uncomfortable situations, it is not a good idea for a woman to ask or demand that a man pay for anything. You don’t want him holding who picked up the tab over your head, or having him demand you give him a taste of your “fruit” later. Speaking for many of the women in my life, and myself, we do not have someone paying our bills. We take care of everything in our own household. And there are some of us who have been doing this thing called life on our own for 15–plus years.

But why is this even an issue?

Adrian Carter Speaks

@adriancarterspeaks

To explore this question, I reached out to conflict resolution practitioner, accomplished poet, ground-breaking author, leadership development trainer, equity consultant, and conflict resolution and life coach Dr. Adrian Carter.

Carter has authored books that address the specifics of what he calls “the fragility toward being held accountable” in the black community, and how he considers the social constructs of gender roles to be “overwhelmingly incongruent and saturated with relationship-ending conflict.”

Carter dove straight into the economic aspect of the issues he sees within this thread. Carter states “The wealth gap between Black and white people continues to widen. Black people are challenged economically, which disrupts how they approach relationships.”

Carter points out that “romance needs finance”, and when there’s a lack in this area of stability, people simply can’t afford to be together under an individualized mindset.

Taking a few moments to elaborate, Dr. Carter made a point that not many of us consider.

“The system of racism and low economics plays a systemic role in the disadvantages we [black people] face. I also believe that Black people have bought into the American version of success more than it is necessary, let alone real,” Carter says.

Like many black Americans, myself included, Carter believes that a house with a white picket fence and a well-paying job does not equate to success. “A Black man and woman can do more together if they work together and not play along into the man–as–provider tradition that no longer serves us,” Carter explains.

“Do you feel that black love is fading?” I asked in my interview with Carter. With dating apps, social media platforms, and blog talk radio shows that focus on black love, are black people losing sight of what constitutes ‘real love’ for us?

“I don’t think Black Love is fading; I think it’s being re-negotiated,” Carter says; he believes the patriarchal idea of man-as-provider and woman-as-housekeeper is an antiquated system.

“Black men and women are also experiencing an ongoing economic plight, which colors their relationship expectations based on their financial needs instead of their social, emotional, and spiritual needs. As women have broken through the glass ceiling of finances and now command higher paying salaries, education, and roles in working America, women and men are rethinking what it means to be lovers and providers,” Carter explains.

He recommends that we [black people] enter into what he refers to as the “We” conversation, one where “We” as black men and women agree to provide for each other and take care of the home together. Carter believes that we should be sharing the responsibility of paying the bills, household chores, cooking the meals and working together as a team. He suggests that traditional submission should be replaced with “submitting to a mission” and to the purpose of the relationship, rather than to the fallible qualities of a human being.

Since the topic of our discussion was dating in the social media post, I asked Carter: what message does he give to his daughters and sons about dating? And what examples does he set for them in regards to what a man should and shouldn’t be to a woman?

“I steer my daughter clear of what to expect from men — she’s only ten years. I don’t take my daughter on father-daughter dates to show her how a man should treat a woman,” Carter says.

“I think we distort the views of young girls with expecting a father as a mate. I want to raise my daughter with character and information about how to be intentional, set goals, be a prayer, listen to the voice of reason in your head, and explore your feelings to know what you want. I want her to also understand reciprocation and how to develop family as a ‘we’ and not as a ‘me.’ Those things will come in time. I display manhood to her through my character. At the moment, she won’t understand all of my decisions. But I look forward to my children as adults because I will make a lot of sense to them then.”

Before parting, I wanted to know what recommendations Carter has for individuals seeking counsel in regard to resolving conflict within themselves, so that they do not project the battles they fight within outward onto their relationships and marriages.

His answer was quite simple.

“A person has to be willing to do the work, starting by asking themselves, ‘What if I’m wrong about everything?’” Carter says.

This starting point refocuses their attention from being the victim (the person who things are happening to). It causes them to question instead, “What if I am the one victimizing others, for whatever reason?”

From here, a person can begin to look in the mirror and practice what Carter calls “radical accountability,” which is explained in more detail in his book “Black Fragility.”

An excerpt from “Black Fragility” reads, “Radical accountability is deep, desperate disruption and inspection of every thought, emotion, decision, idea, lifestyle choice, and practice you have undertaken to learn how you arrived at your current station in life. I think of radical accountability as an aggressive, intense determination to find the source code of malware in your way of acting, thinking, and behaving.” Carter believes this approach to accountability leads to self-discovery and, hopefully, to becoming someone who is able to take the lead in their own life holistically.

I believe that a relationship or marriage is like a box; you cannot get anything from it if you are not putting anything into it. No one can expect to receive anything from their partner that they are not willing to give. If someone fails to feel at peace within themself, then they will not be able to outwardly recreate a peaceful environment with their partner. This level of peace is only achievable when a period of truthful and honest self-reflection has given rise to the blessings of self-control, respect for others, and awareness of one’s emotional blind spots. Taking accountability for one’s actions is not about guarding one’s self from what may happen with a potential lover or spouse. It is about making sure that your actions towards others does not make you the common denominator in all of your failed relationships in the past.