Since 1987, the Beit T’Shuvah thrift store in Culver City has been “a high-end, charity-run resale store that supports Beit T’shuvah, a drug/alcohol rehab in Los Angeles,” as described on their Google profile. The store places emphasis on the value of charity, hiring primarily recovering addicts in its storefront. Over Thanksgiving, I visited the store only to find that it was involved in a confusing partnership with the Church of Scientology.

While shopping at the store, I purchased a documentary called “The Truth About Drugs.” I was drawn in by its garish cover and D.A.R.E. moralism—according to the back of the DVD, meth is normally made from “battery acid and rat poison.” Frankly, I thought watching it would make a good laugh, along with the other documentary I got that would walk me through surviving singlehood as a Christian woman. As a documentary, “The Truth About Drugs” is unsurprisingly lackluster. The film lacks any narrative structure, playing like a series of interviews with real people, not actors, lit with an ominous green filter. The documentary makes outrageous claims about the nature of drug use; it claims that marijuana leads to crack and heroin, or even that sniffing glue is a common adult method of inhaling drugs—but even the absurdity of the documentary’s claims couldn’t make it stand out. Instead, it blended into the memory miasma of every other scared-straight anti-drug documentary I’ve ever been forced to watch.

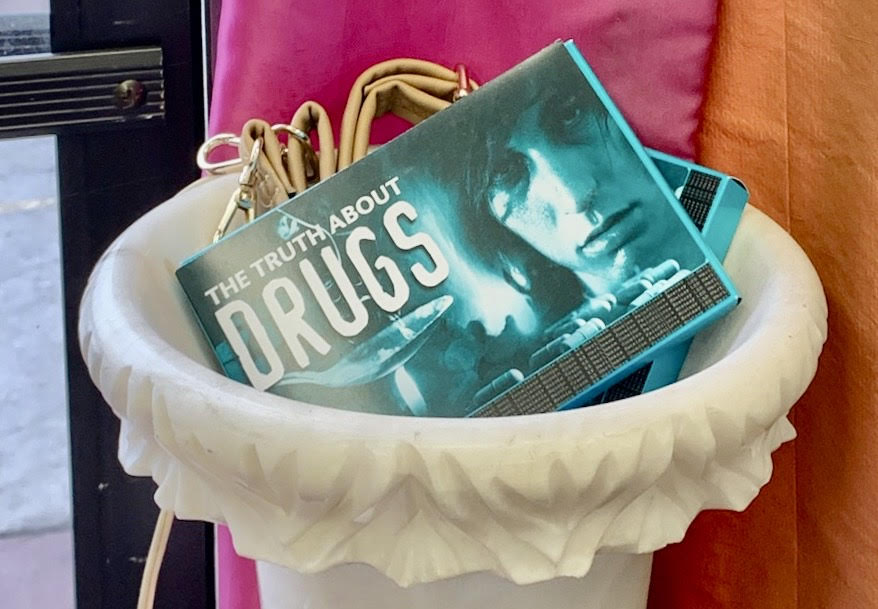

According to the cashier, purchase of the documentary “The Truth About Drugs,” as well as any of the corresponding pamphlets by the door of the shop, would go to “charity.” Perhaps they meant the organization that made the documentary, The Foundation for a Drug Free World—which, according to Marty Tofil of Scientology’s notorious rehab center, Narcanon, is a Scientology subsidiary. However, neither the cover of the documentary nor the pamphlets give any clear indication of their association with Scientology, to the point where I began to doubt whether Beit T’Shuvah themselves even had any knowledge of the documentary’s connection to the Church. When I called, no one at the thrift store one seemed to know much about the partnership, or even about the basket of “The Truth About Drugs” pamphlets by the door of the store.

According to Sergio Rizzo-Fontanesi, of Beit T’Shuvah’s parent rehab organization of the same name, the thrift store is part of a “wraparound service approach” to drug rehab. A place like Beit T’Shuvah’s thrift store “helps people reintegrate into mainstream life [with] job training and jobs. … [One of Beit T’Shuvah] primary social enterprises … is the thrift store run by former residents,” meant to give them an opportunity for employment and sobriety.

According to their website, the Foundation for a Drug-Free World is “is a nonprofit public benefit corporation that empowers youth and adults with factual information about drugs so they can make informed decisions and live drug-free.” The 2008 documentary—along with the organization’s media generally—is, according to employee Neil Patrick, “basically just trying to reach particularly young people, mainly because they get a lot of influences on television, even from friends, [telling them that] if you do drugs it’s cool, [and that] it’s a grown-up thing to do.”

Patrick explained that rehabilitated people who have worked with the organization will “themselves … pass out information,” describing the dissemination of the organization’s literature as a “grassroots type thing.” When asked whether it was possible that a rehabilitated individual involved with both the foundation and with Beit T’Shuvah had placed the pamphlets in the store, Patrick said it could “very well could be somebody, but we have no idea,” going on to remind me that “anybody can come on [The Foundation for a Drug Free World’s] website and order [its] materials. If someone wants to use the materials and use them in their organization, we don’t really care.”

As of now, the connection between Scientology and Beit T’Shuvah remains a mysterious, and possibly very unintentional, conspiracy of silence—for which hope of enlightenment lies in the generosity of the Scientology representatives I have contacted, but have not yet responded to me.