On May 3, 1990, approximately 400 students, staff and faculty members were gathered on Toyon Meadow after being “tolled in” by the bells of the El Campanile tower, according to the July 1990 issue of the Mills College Quarterly.

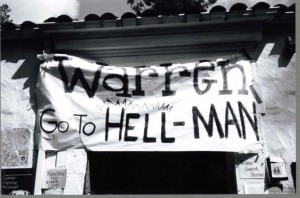

Board President Warren Hellman then announced to the student body that the Trustees had voted to admit men into undergraduate programs. The rest of his announcement was drowned out by cries and jeers of protest as students reacted to the news.

Former President Mary Metz and Dean of Students Patricia Polhemus attempted to speak, but their words weren’t heard by students, who had already begun engaging in the civil disobedience that would last for the next 16 days.

Then-ASMC President Robyn Fisher grabbed the microphone and told the enraged student body, “You have been betrayed. This is a women’s institution and we will not accept this.”

Warren Hellman later said in an interview that a significant majority of the Board voted to allow men at Mills. The Eugene, Oregon Register-Guard reported nearly a two-thirds majority.

The Board cited lagging enrollment and financial instability as reasons for its decision — according to the Houston Chronicle, Mills needed to add $10 million to its endowment to remain in operation.

The plan had been in the works for almost the entire school year, as the Board had known Mills was financially unstable for some time. From the last two decades, since the early 1970s, the school had a difficult time increasing the size of its entering class, according to the campus newspaper The Weekly.

A task force had been set up in the fall of 1989 to work with the administration and the Board to find ways of relieving mounting its financial instability. In September of that year the student body was first informed by The Weekly that becoming coeducational was a “major option.” Other options mentioned were cutting faculty and staff and expanding programs and enrollment.

However, at a Nov. 3 Board meeting, the Trustees had eliminated all but two options: coeducation and expansion. Of these two, the Board felt expansion seemed a “weaker” choice.

By December 1989, students had started protesting the coed option — the Dec. 1 issue of The Weekly showed Senior Class President Melissa Stevenson-Dile wearing a shirt bearing the now-infamous slogan, “Better dead than coed.”

The Board meetings continued until the Trustees announced their decision on May 2.

“I do not believe that a single Board member voted in support of the resolution because he or she wanted Mills to become a coed college,” said alumna Mara Michelle-Batlin, class of 1983, who was a member of the Board at the time.

Within hours of the announcement that Mills would become coed, close to 400 students mobilized and voted to close down the College to protest the decision, and by the next day, the Strike was in full effect. Students shut down five buildings by physically blockading their 19 doorways. A sign located at the front of Richard’s gate simply said, “Closed for repairs,” according to the Quarterly.

“The students stopped the clock, stopped the process and gave everyone time to work on a solution,” Metz later said.

While the students shut down the campus, they “redecorated” with colorful banners, posters and fliers, all heavily adorned with the female symbol and slogans like “We do not accept this,” “138 years: Why stop now?” and “Women’s education for the next generation.” Yellow become the color to symbolize the protest.

“The is BABY FEET. We have ALAMO at ALCATRAZ. MR. HAND is at it. GERONIMO 50!”

In radio code used during the Strike translates to:

“This is Alexa. We are under attack at Alderwood.

Dave Johnson is trying to get in. We need people asap. About 50!”

— Alexa Pagonas, via Facebook. Dave Johnson was the Grounds Manager during the Strike.

Many students did not go to class in the last days remaining before the end of the semester, while some professors held class outside to accomodate them. Administrative officers were prevented from entering their offices and were first relocated to a hotel, then to private homes.

Alumnae played a huge role in the Strike. Within two days of the coed announcement, the Mills Alternative Alumnae Coalition (MAAC) formed to protest the decision and to act independently from the Associated Alumnae of Mills College (AAMC), who promised to go along with what the Board decided.

Members of the MAAC quickly mobilized, contacting all alumnae in the Bay Area, organizing meetings and even planning a picnic to rally alumnae for the fundraising effort about to ensue — after their takeover of Reinhardt Alumnae House.

Alumnae also aligned themselves with the striking students by walking the barricades and helping with anything the students needed, everything from supplying extra supplies to animal crackers and frozen yogurt.

“I went home and made up pots of mashed potatoes,” Cynthia Waggoner, class of 1972, recalled.

Parents, faculty and staff from dining services also joined the catering effort and, according to Fisher, it became a joke that this was the first “catered-in” Strike.

By day six of the Strike, the faculty, staff and Board of Trustees began working on a proposal that would allow Mills to remain a women’s college. During this time, alumnae and students embarked on a fundraising plan to increase alumnae donations by 50 percent within five years.

In the course of the first week, about 150 Strike participants contacted approximately one-third of the College’s alumnae and raised more than $3.1 million in pledges. According to the Quarterly, more than 70 percent of those reached said donated money.

Ray Beldner, who received his MFA in 1989, said not one person turned him down. Beldner became part of a group called “Men Against Men” made up of male graduate students and community members opposed to the coed decision.

Students ended the Strike on May 17 upon hearing the Board would be making some kind of announcement the next day.

On May 18, the Board met from 9 a.m. until 1 p.m., at which time its declaration that it was reversing its decision was announced. This time, Hellman’s words were met with cheers instead of boos. He helped unfurl a banner which read “Mills. For Women Again.”

Even after the fundraising effort, there was still a lot of work to do. In addition to increasing the endowment, professors had to teach an additional course each semester without additional pay, and everyone agreed to do his or her part to raise the school’s enrollment from 777 to 900 students by 1993. By 1995, the figure had to reach 1,000 students, or the Trustees would reconsider its decision.

The school achieved these requirements, almost tripling the endowment over the next two decades, and steadily increased enrollment year by year.

Today, despite a downturn in the economy, Mills is thriving as a women’s college because of the work the alumnae and students did in those 16 days 20 years ago.

Check out the authentic documents distributed to students during the Mills Strike. Provided by Mills alumna and Striker, Alexa Pagonas:

Read more related Strike articles here.