BUFFALO, N.Y. WIVB reports that former Buffalo police officer, now-activist, Cariol Horne (53) was fired from the Buffalo Police Department 12 years ago when she stopped another officer’s chokehold on a suspect. She hadn’t received her pension benefits and has been a very outspoken advocate for police reform.

On Tuesday, April 13, 2021, Hon. Dennis Ward vacated the ruling that supported her firing and made it impossible for Horne to appeal the decision. Horne’s crime: in 2006, he intervened while a white colleague, Greg Kwiatkowski, was violently arresting a Black suspect, Neal Mack. The Buffalo Police Department ruled in Kwiatkowski’s favor following a 2007 internal investigation, and Horne was fired in 2008, just one year shy of the required 20 years of service needed to retire and receive a full pension. Horne received national attention when she appeared on media outlet CBS This Morning defending her actions.

“I don’t want any officer to go through what I have gone through,” Horne said. “I had five children and I lost everything but [the suspect] did not lose his life. So, if I have nothing else to live for in life, at least I can know that I did the right thing and that Neil Mack still breathes.”

According to WIVB, Buffalo Common Council president, Darius Pridgen, asked the State Attorney General to review Horne’s case.

“We now have a totally different attorney general, we have a total different climate and atmosphere and lens right now, across this world, as it deals with policing in the United States,” Pridgen said. “So I think it’s an opportune time to look back at this case and to see where the civil rights violations can be made whole.”

Following many years of long drawn out litigation, on April 13, 2021, WKBW reports that a New York State Supreme Court ruling has reinstated Horne’s pension, and she will receive backpay and benefits, following a decision by Hon. Dennis E.

NPR reports another former officer story, back in June 2020, former Chicago police officer Lorenzo Davis won a $2.8 million dollar judgment after he was fired from the police review board. He was serving as a civilian member when he says his employment was terminated for refusing to change his investigative findings on police misconduct.

“I was interested in what I was reading in the daily newspapers about officer-involved shootings. I did not recall it being so many when I was – the 23 years that I was a police officer,” said Davis. “So I was interested in finding out exactly what was going on in the city of Chicago, my city. And I began to find that there was a lot of misconduct that was being committed, and police officers were not being held accountable for it.”

Davis stated that when the administration of the agency where he was employed changed, a new chief administrator came in who was a retired DEA agent and a member of the federal Fraternal Order of Police. “It was at that time that my reports were being rejected,” says Davis.

Davis told NPR that the new chief administrator accused him of being “biased against police officers” and ordered him to change the report’s findings. Davis refused, stating that he would have to “change the evidence and witness statements,” which is against the law.

Similarly, former Chicago police detective Sergeant Ike Lambert was retaliated against when he refused to sign off on falsified police reports.

“Basically, after a year or so, when the report and its investigation remained dormant, a FOIA request was submitted to the city of Chicago, which prompted action by my police department,” said Lambert. “I’ve always spoke up against things I thought was wrong within the department. But this culture right now, a lot of officers don’t feel as though they can speak up because there’s no real, true mechanism that protects us from retaliation from our superiors.”

What these three former officers all have in common is the use of their voice when speaking out against injustices within law enforcement, and the reprisal that has followed as a result. The Baltimore Sun reports that the Department of Justice conducted their own investigation into retaliation claims from former and current police officers. The findings highlight what was described as “an internal culture of intimidation and retaliation” that closely resembles the “no snitching” mantras some drug dealers use to intimidate potential police informants. Several officers told the Justice Department investigators that they believe they have experienced or will face retaliation from fellow officers for “reporting misconduct or objecting to improper enforcement activities” on the job.

It is not just the inter-department retaliation that keeps good officers from standing up against injustices that both police and civilians face, its the working relationship that police share with prosecutors that serves as an added layer of difficulty that blocks fair and balanced policing.

The American Civil Liberties Union, or ACLU, recently argued in the Boston University Law Review that the codependent relationship between prosecutors and police prevents accountability for police violence and misconduct against American citizens and fellow police officers, specifically, when analyzing:

- The cultural norms that have created a consensual dynamic between police and prosecutors that make it possible for police to influence prosecutorial discretion over police accountability.

- The legal and extralegal tools that prosecutors wield in efforts to protect their police benefactors and themselves in the process.

The police and prosecutor relationship enables the habitual line-stepping practices of police brutality and

An example of this is former commander of the Chicago Police Department, and well-known racist, Jon Burge, who tortured over 120 Black men in Chicago in the 1980s and 1990s by placing bags over their heads, burning them with cattle prods and shouting the n-word while electrocuting them. Burge forced these men to make false confessions through barbaric means, and the Cook County State’s Attorney failed to hold him accountable for these wartime methods of interrogation. Chicago prosecutors continued with Burge’s case, failing to disclose to jurors the methods of torture he used for unlawful confessions. In doing so, prosecutors displayed

The ACLU’s report states that “prosecutors validated a formalized process through which police could operate with nearly unchecked oversight and prosecutors could reap the ‘benefits’ of high conviction rates and long sentences. These benefits are both political and structural.” The end result is higher conviction rates on violent cases that give the smoke and mirrors effect of being “tough on crime.”

Convictions won at trial with police testimony also provide a kind of accreditation in the State’s Attorney’s Office that earns prosecutors their promotions. There are no statute or common law that manages the rules of engagement between everyday citizens, the police and officers of the court. This allows the unchecked institutional norms of practice and incentives are so entrenched in modern-day policing that they enable police misconduct to operate with near impunity, resulting in low conviction rates for police officer who violate the constitutional rights of American citizens.

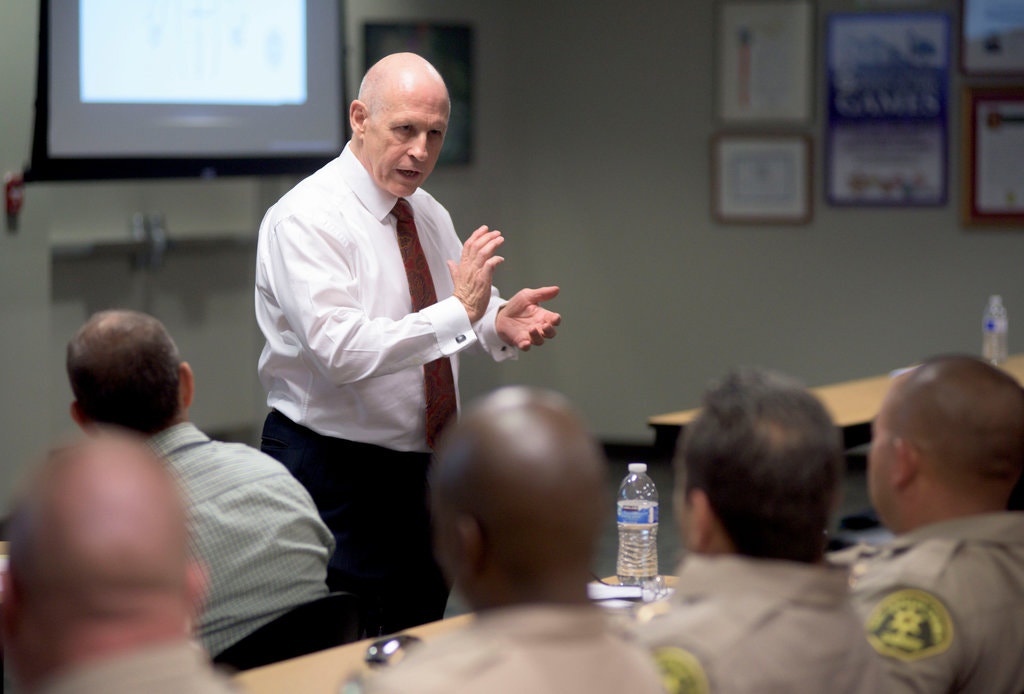

Then there’s the convenience of expert witnesses on behalf of law enforcement. For example, Dr. William Lewinski at the Force Science Institute in Minnesota preaches that a cop should learn to become more lethal while on the job. Dr. Lewinski is one of the most influential voices and supporters on the topic of police-involved shootings and has testified or been consulted for input in nearly 200 police shooting cases over the last decade. He has single-handedly assisted with justifying countless shootings around the country, with a consistent conclusion: the officer acted appropriately, even when the victim was unarmed, was shot in the back or when forensic evidence/video footage contradicts the officer’s story. According to the New York Times, The Justice Department denounced his findings on the basis of “lacking in both foundation and reliability” and civil rights lawyers say he is selling dangerous ideas to law enforcement.

John Burton, a California lawyer who specializes in police misconduct cases, said “People die because of this stuff, when they give these cops a pass, it just ripples through the system.”

The New York Times reports that in 2012, the Justice Department paid Lewinski $55,000 to help defend a federal drug agent facing charges for shooting and killing an unarmed 18-year-old in California. Then in 2014, as part of a settlement over excessive force, the Seattle Police Department endorsed sending officers to Lewinski for additional police training. And in 2015 Lewinski was paid $15,000 to train U.S. federal marshals.

Kristina Roth, a criminal-justice researcher at Amnesty International, told Insider that officers who shoot and kill civilians are even more infrequently convicted.

“Deadly force should be reserved as a last resort, and that force should be necessary and proportional. There’s no state that meets [that] standard,” said Roth.

There were more than 1,000 “known police killings” every year from 2013 through 2019, most of them shootings, according to Mapping Police Violence. The word “known” is used loosely because the accuracy of the numbers reported cannot be validated since some law enforcement agencies do not report all police-involved shootings (and the deaths as a result) to the Justice Department.

According to Vox, there are many social and legal factors that contribute to the low conviction rates for police who violate constitutional rights and break the law. These factors can range from the cultural pressure cops face to protect fellow officers, even when those officers are wrong, to prosecutors facing a conflict of interest when they risk aggravating police departments they work with by pursuing charges against corrupt police. This makes it more difficult to report wrongdoing at every phase of an investigation into a police shooting.

During the standard after-action process following a murder, police are required to gather evidence of a crime, collect physical materials and talk to witnesses. Then prosecutors use that evidence to build and try their case in court. From there, a suspect can then make a deal and plead guilty, or take the case to trial. But in the case of a police-involved shooting, things work a differently.

According to George Washington Law in Washington, D.C., police officers and ordinary citizens are entitled to use deadly force in cases of self-defense and/or when there’s a reasonable fear that their lives are in danger. The catch-22, in this case, is that civilians cannot claim self-defense, if they were deemed by police responding to an incident as being the “initial aggressor” during an encounter turned violent. In most states the on-duty police officers cannot be considered aggressors. The Marshal Project states that in such cases, the officer still won’t be held accountable for their actions, even if they create or escalate a dangerous situation.

Most states can’t engage police officers in legal actions because of what’s called the “Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights” — a set of guidelines intended to protect American law enforcement personnel from investigation and prosecution arising from conduct during the official performance of their duties and provides them with privileges based on due process.

The bill is a redefined version of the Bill of Rights assuring police officers will receive treatment that they do not consistently offer to suspects they are questioning or detaining. It was first set forth in 1974, following supreme court rulings in the cases of Garrity v. New Jersey (1967) and Gardner v. Broderick (1968). The objective of the bill was to protect police facing persecution for performing their duties but is now being used to assist with court acquittals.

Fourteen states have a Law Enforcement Officers Bill of Rights: California, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Virginia, West Virginia and Wisconsin.

Some of the common provisions in the measures vary from state-to-state and include:

- Investigators may not harass, beat, threaten or promise rewards to the officer during the interrogation process. These are constitutional rights that police interrogators do not infrequently honor with civilian suspects.

- In Maryland, the officer may appeal his case to a “hearing board,” whose decision is binding. This can happen before a final decision has been made by their superiors about their discipline. The caveat is that the hearing board consists of three of the suspected offender’s fellow officers.

- In some jurisdictions, the officer may not be disciplined if more than a certain number of days (in most cases 100 total) have passed since his alleged misconduct. This limits the time for a serious investigation to be conducted.

- Even if the officer is suspended, the department must continue to pay salary and benefits, including the officer’s legal fees.

Many police shootings are ruled justifiable when dealing with a suspect who was deemed a serious threat to the safety of the officers involved, or any civilians nearby. This is why most police officers will make the statement that they felt “threatened” or they “feared for their life” after a fatal shooting.

Some cops resist treating a police shooting as a crime and refuse to gather evidence. In doing so, they are mostly likely adhering to what The New York Times called the “blue wall of silence,” which is essentially an unwritten code between officers that they won’t testify against each other in legal proceedings or try to get each other in trouble. As a result, the cops who are often the closest witnesses to fatal shootings will refuse to provide an accurate account of the incident if it puts their colleagues in danger of prosecution. This “no snitching” culture eliminates fellow officers from becoming witnesses to a crime.

Horne, Davis and Lambert are just a few examples of police officers who’ve faced the consequences of speaking out against the normalized practices of police brutality and flat-out murder in broad daylight. And Dr. Lewinski demonstrates how the “blue wall” is carefully safeguarded within the legal system. According to The Project On Government Oversight (POGO), American society enacts strict punishments upon the average citizen accused or convicted of committing crimes, but when police officers, prosecutors and government officials break the law and violate American citizens’ constitutional rights, they are often acquitted of any charges they may face. This is because individuals who take legal action against police brutality are forced to expend countless amounts of manpower, money and time trying to navigate the legal system when seeking justice.